Processes fall into four different categories for operations management based on the nature of their function. Some processes relate primarily to a product’s cost structure; others address the company’s product standardization needs, output volume, or production flexibility. Take a look at processes that focus on these types of business considerations and review general guidelines on how to best select a process to meet the requirements of your product.

Before you dive into classifying a process, consider the nature of the product it’s intended to produce. After all, creating a unique item, such as an interstate highway bridge, is wildly different from producing a million bottles of contact-lens solution or thousands of socks in two different colors. Here are common process classifications, arranged according to fixed costs (lowest to highest):

Projects: These generally result in an output of one. Examples include constructing a building or catering a party. Although the result of a project is one deliverable, the process of creating the item can be duplicated with modifications for other projects.

Job shops: This type of process produces small batches of many different products. Each batch is usually customized to a specific customer order, and each product may require different steps and processing times. Examples of job shop products include a bakery that specializes in baking and decorating wedding cakes, each one customized for a bride, or a programmer that creates customized websites for his clients.

Batch shops: These produce periodic batches of the same product. Batch shops can produce different products, but typically all the products they produce follow the same process flow.

A facility producing shirts of different sizes and colors or a bakery preparing different flavors of cakes or types of cookies are examples of batch shops. These processes make one type of shirt or cookie in a batch and then switch to a different type, but all types follow the same flow.

Batch shops usually require some setup time — time required to prepare resources to produce a different type of product.

Flow lines: This type of process consists of essentially independent stations that produce the same or very similar parts. Each part follows the same process throughout the process. Output on a flow line is dictated by the bottleneck, or the slowest operation. The flow line is similar to the assembly line but the parts don’t move at a constant rate dictated by the line speed.

The terms flow lines and batch shop process are often erroneously used interchangeably.

Assembly lines: These produce discrete parts flowing at controlled rates through a well-defined process. The line moves the parts to the resources, and each resource must complete its task before the line moves on. This requires a balanced line, meaning that each operation completes its task in a similar amount of time. The line moves at the speed of the slowest operation, or bottleneck.

Continuous flow processes: As the name implies, these processes produce items continuously, usually in a highly automated process. Examples include chemical plants, refineries, and electric generation facilities. A continuous flow process may have to run 24/7 because starting and stopping it is often difficult.

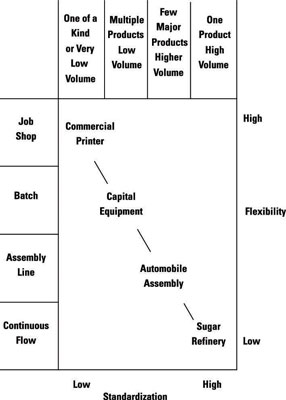

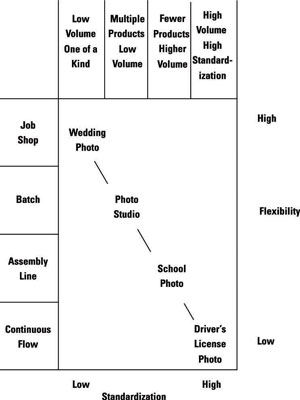

Take a look at where each process falls on the standardization, volume, and flexibility matrix for both products and services.