Before getting into the nitty-gritty of process costing, you may benefit from reviewing a few basics — namely, how to use debits and credits, how to keep track of the costs of goods that you make and sell, and how goods and their costs move through a typical production line.

Enter debits and credits

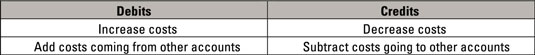

Remember that when costing goods, almost all accounts are either assets or expenses, such that in most cases, debits increase balances and credits decrease balances. Accordingly, when using T-accounts, increases go in the debit column on the left, while decreases go in the credit column on the right.

Liabilities, such as Accounts payable and Wages payable, go in the opposite direction. Debits decrease these accounts, and credits increase them.

When you’re costing goods, journal entries transfer balances between different accounts.

Keep track of costs

Products have three different kinds of costs:

Direct materials: The cost of materials that you can easily trace to manufactured products. For example, if you’re making peanut butter sandwiches, direct materials include three ounces of peanut butter and two slices of bread per sandwich.

Direct labor: The cost of paying employees to make your products. Direct labor for making peanut butter sandwiches includes the cost of paying employees for the five minutes they take on average to prepare a single sandwich.

Overhead: All other costs necessary to make your products. For peanut butter sandwiches, overhead includes the costs of running the kitchen, including utilities and cleaning.

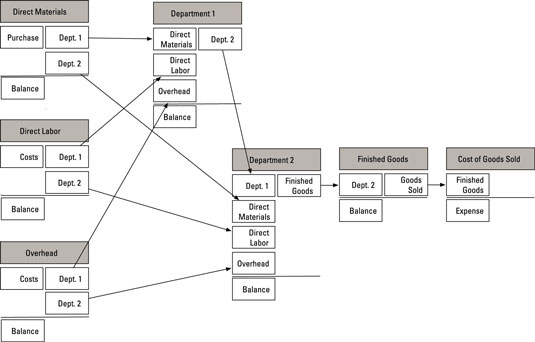

Accountants need to first accumulate costs and then assign them to individual departments. The road map here shows how debits and credits steer through the accounts.

Move units through your factory — and through the books

In mass production, goods move through different factory departments until they’re completed.

Suppose your factory makes T-shirts. One department cuts the fabric and then sends it to a second department, which sews the cut pieces together. A third department then folds and packages the T-shirts into plastic bags. Then you can call the completed goods finished goods because they’re ready for sale.

As goods move through production, their costs move through the company’s books. As the factory moves direct materials into the Cutting department, use journal entries to move the cost of those direct materials out of the Raw materials inventory account and into the cutting department’s work-in-process inventory account.

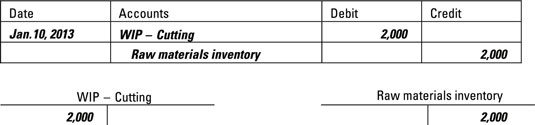

Therefore, you debit/increase the account WIP Cutting department, which gets the direct materials, and you credit/decrease the account Raw materials inventory, which gave up the materials.

Here, the account that represents the cost of WIP in the Cutting department increases by $2,000, while the cost of Raw materials inventory decreases by $2,000. This transfer moves $2,000 out of Raw materials inventory and into the Cutting department’s WIP.

From here, you continue to record similar journal entries to keep track of inventory as it moves through different departments.