The breeds in the first group, the Oriental, are notable for their long, sleek bodies and active participation in the world around them. They’re not happy unless they’re supervising dinner, climbing to the top of the bookshelf, teasing that dopey dog, or seeing what every member of the household is up to. The way these cats see the world, you’re not capable of running your own life without their help. Cats in this group, such as the Siamese, and Abyssinian, are often touted as being more intelligent and trainable, as well as the Oriental Shorthair, basically a Siamese coat but with a broader range of coat patterns and colors

The non-Orientals see things a little bit differently. If you’re big and beautiful, the world comes to you with all your needs. Why interrupt a good nap to see what’s on top of that bookshelf? Cats in this group, such as the Persian, Ragdoll, and British Shorthair are generally happy to sleep in your lap while you read — and not bat at the pages as you turn them!

At first, the differences between these breeds may also seem to relate to their coats, with the sleek shorthairs falling in the Oriental group and thicker-set longhairs in the other. That assumption would be true except for the work of those who want to offer you even more options in a cat, such as longhaired versions of the Siamese (the Balinese) and Abyssinian (the Somali) and a breed that’s pretty close to a shorthaired version of the Persian (the Exotic).

The history and legends behind the various breeds of pedigreed cats are almost as interesting and colorful as the cats themselves. Two books that are good jumping-off points for more in-depth research into cat breeds are The Cat Fanciers’ Association Cat Encyclopedia (Simon & Schuster) and Cat Breeds of the World: An Illustrated Encyclopedia, by Desmond Morris (Viking). The handful of registries of pedigreed cats all have websites that provide additional information on the breeds in each association.

Unlike purebred dogs — who are divided roughly by purpose: sporting, herding, and so on — pedigreed cats aren’t quite so easy to categorize. Not surprisingly, really, if you consider that each cat himself is unique — and if you don’t believe it, just ask him!Not happy with the two divisions the experts offer, we break down the various breeds into categories, a task almost as difficult as herding cats themselves. The breakdown’s not perfect — some longhaired cats are also among the largest, for example, and some of the more active breeds are also distinctive in other ways. (In such cases, we list the breeds twice, once in each category.) But we figure that breaking the almost 50 breeds down into categories would make thinking about what sort of breed you may want a little easier.

The go-go group

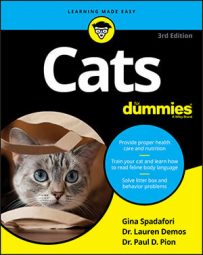

Consider the Siamese (shown in the following figure) the prototype of this group. Always into everything, always looking to see what you’re up to, and always loudly suggesting ways you can do it better — these characteristics are the essence of this cat, one of the world’s most easily recognizable breeds with his distinctive “pointed” markings. The Siamese is such an important breed that its genes went into the development of many others, such as the Himalayan (a pointed version of the Persian); the Balinese (essentially a longer-haired Siamese); and the Birman, Burmese, Havana Brown, Ocicat, Oriental Shorthair (a Siamese in solid colors and total-body patterns), Colorpoint Shorthair (a Siamese with more options in point colors), and Tonkinese. Not surprisingly, many of these breeds — the Himalayan alone not among them — are also high on the activity scale. You couldn’t get these cats to sit still for a photograph! Active breeds include the Abyssinian, Burmese, Cornish Rex, and Siamese.

You couldn’t get these cats to sit still for a photograph! Active breeds include the Abyssinian, Burmese, Cornish Rex, and Siamese.A cat doesn’t need to be Siamese — or related somehow to the Siamese — to be above-average in terms of being on the go. Not as talkative generally, but just as busy, is the Abyssinian, with markings that suggest a mountain lion and a reputation for being one of the most intelligent and trainable of all breeds. Other breeds with energy to burn are the Bombay, the kinky-coated Cornish and Devon Rexes, the Egyptian Mau, the Somali (a longhaired Abyssinian), and the hairless Sphynx.

Although these breeds can be a constant source of amusement with their energy and fearless ways, they can also be a handful. You should be prepared to endure cats on the drapes — the better to get up, up, up! — and kittenish behavior that endures for a lifetime. These cats never stop and are as likely to want to play at 2 a.m. as at 2 p.m. They surely want to be with you all the time, but on you? That’s another matter. Lapsitter kitties these are generally not — they’ve got things to do!

The people who choose these breeds do so for a reason: They’re fun! If one of these cats is in your future, get a good cat tree and lay in a huge supply of toys, because you’re going to need them.

A touch of the wild

One of the many things we humans find appealing about cats is that, even in the most tame and loving of our household companions, a touch of the tiger remains. Indeed, the tiger’s stripes remain on many of our pets, reminding us always of the connection — a reminder strengthened whenever you watch a cat walk, run, or leap. The grace and power are the same for big cats and for small.Our cats may have chosen domestication, but on their own terms. And always, always, with a little bit of wildness held in reserve.

That we love this essential wildness is apparent in our long-standing interest in cat breeds that retain the look of the wild about them — not with the “ordinary” tiger stripes of the tabby but with spotted coat patterns evocative of another great wild cat, the leopard.

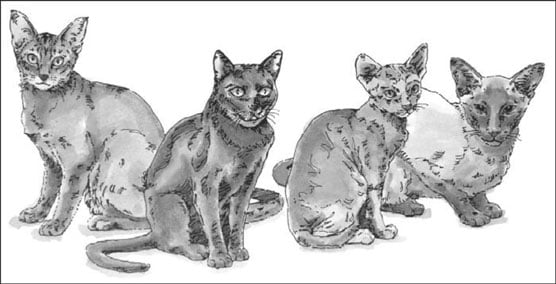

Most cats with a spotted “wild look” haven’t any wild blood in them at all — they’re the results of breeders trying to develop coat patterns that resemble the domestic cat’s wild cousins. You can put into this category the Ocicat, derived from breedings of the Siamese and Abyssinian and named for the Ocelot, which it resembles. The Egyptian Mau (Mau means cat in Egyptian) is another spotted wonder, a lovely cat bred to resemble the cats seen in ancient Egyptian artwork.

The Bengal, Egyptian Mau, and Ocicat evoke the beauty of the Leopard with their spotted coats.

The Bengal, Egyptian Mau, and Ocicat evoke the beauty of the Leopard with their spotted coats.A cat of a different variety altogether is the Bengal, a cat developed through breedings of domestic cats with wild Asian Leopard Cats. Fanciers say the wild temperament has been removed by generations of breeding only the most sociable and friendly Bengals, although the look of the wild cat it came from remains. The Toyger is a litter easier to live with for many people without the cross to wild cats. They’re a smaller than Bengals but maintain the wild look without the wild breeding.

The Bengal and other breeds that have been crossed with undomesticated feline species come with responsibilities that many people aren’t prepared for. They can be quite wild and difficult to handle, so much so that Dr. Lauren notes that many veterinarians would strongly recommend that people generally think twice before adopting one of these breeds.

The temperament of these “wilder” breeds generally lies somewhere in the middle between the go-gos and the more easygoing breeds, which we discuss next. They’re not placid layabouts, but neither are they as active as some breeds. For those who love the look of a leopard in a manageable, loving package, these cats are perfect.Longhaired beauties

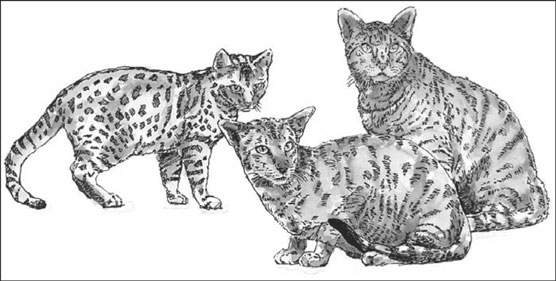

The Persian is the other cat besides the Siamese that nearly anyone, cat lover or not, can recognize. The incredible coat of this breed has enchanted cat lovers for centuries. Whenever companies look for a breed that says “glamour” to use in their advertising, that they often settle on a Persian is no accident. This cat is a glamour-puss, no doubt about it (see the following figure). The Birman, Himalyan and Persian are all cherished for their luxurious, long coats.

The Birman, Himalyan and Persian are all cherished for their luxurious, long coats.Perhaps no cat besides the Persian comes in as many varieties, each cat resplendent in that incredible coat: tabbies of every color, torties, calicos, every imaginable solid color, and tipped coats, too. The markings of the Siamese can be found in the Himalayan, which in cat shows is considered a pointed Persian.

If you’re looking for a more natural longhair, you have plenty of options. The Turkish Angora and Turkish Van are two ancient longhaired cats. The Norwegian Forest, Maine Coon, and Siberian cats are longhairs that still have the rough-and-tumble look of farm cats about them. And don’t forget the Birman, the sacred cat of Burma, a breed that looks somewhat like a Himalayan, with color darker at the points, except for the perfectly white-mitted paws.

The Ragdoll is another pointed longhair with white mittens of more-modern origins — it was “invented” in the 1960s — and is another choice for those seeking a longhaired cat, especially one designed to have an extremely laid-back temperament. Another lovely longhair with a relatively short history is the Chantilly/Tiffany, a cat with silky hair, commonly chocolate colored.

In the longhaired ranks, too, are a few breeds you can distinguish from their better-known relatives only by the length of their coat. Put in this class the Cymric, a longhaired version of the tailless Manx, as well as the Somali (a longer-haired Abyssinian), Balinese (a longer-haired Siamese), and Javanese (a longer-haired Colorpoint Shorthair).

The biggest challenge facing those who own longhaired cats is coat care. The long, silky coat of the Persian mats easily and requires daily attention to keep it in good form. Other longhaired coats aren’t quite as demanding, but they all require more attention than the coats of shorthaired cats. And they all shed rather remarkably! Ingested hair, commonly called hairballs, is a bigger problem in longhaired cats, too.

The temperament of longhaired cats depends on what’s underneath that lovely coat. If an Oriental body is underneath — such as in the Balinese — you’ve got an active cat. The larger, more thickset body types, such as those of the Persian and Norwegian Forest Cat, tend more toward the laid-back end of the spectrum.The big cats

Although you’ll never see a pet cat as big as a St. Bernard — or at least, we certainly hope not — a few breeds definitely warrant the heavyweight category where cats are concerned. Although most healthy cats — pedigreed or not — weigh between 8 and 12 pounds, some of the big cat breeds range between 15 and 20 pounds, especially the males. Now that’s a cat who can keep your lap warm on a winter night!The biggest domestic cat is thought to be the Siberian cat, with some males topping 20 pounds. This breed is pretty rare, however, so if you’re looking for maximum cat, you may want to consider the Maine Coon or maybe the Norwegian Forest, another longhaired chunk of a cat. Other longhaired cats with an above-average size include the Ragdoll, Turkish Van, and American Bobtail (see the following figure).

The Turkish Van, Maine Coon, and British Shorthair are perfect breeds for those who like their cats large.

The Turkish Van, Maine Coon, and British Shorthair are perfect breeds for those who like their cats large.For a lot of cat without the fur, consider the British Shorthair, the American Shorthair, and the Chartreux.

The large cats are generally fairly easygoing in temperament and more laid-back than many other breeds. If you’re looking for a more active and involved pet, these breeds are not the ones for you.

A brown tabby Maine Coon named Cosey won the first major cat show in North America, held May 8, 1895, in New York City’s Madison Square Garden. The engraved silver collar and medal presented there is now the most important piece in the Cat Fanciers’ Association’s collection of cat memorabilia and art.

Something different

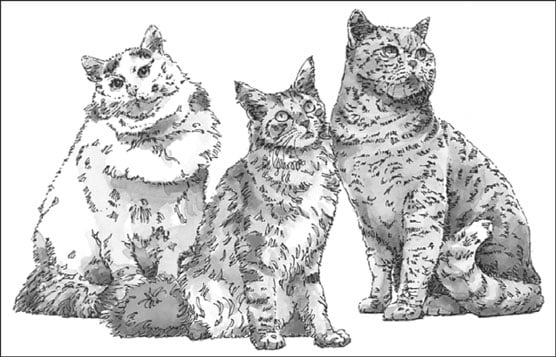

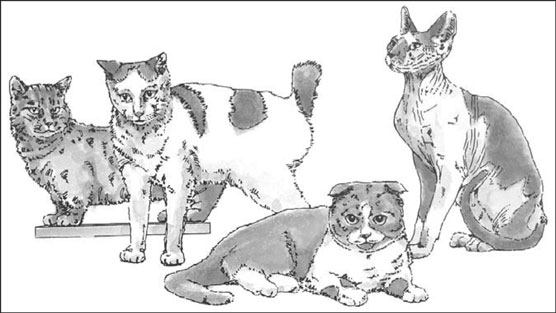

New cat breeds are created all the time, some by accident, some by design. Many cat breeds start after someone notices a kitten with something “different” — ears, legs, or other characteristics that set him or her apart from other cats. These cats, shown in the following figure, are some of the rarest around and among the most controversial. They’re also among the most expensive to acquire — if you can find one at all. The short-legged Munchkin, short-tailed Japanese bobtail, ear-altered Scottish fold, and nearly hairless Sphynx are all certain to start a conversation.

The short-legged Munchkin, short-tailed Japanese bobtail, ear-altered Scottish fold, and nearly hairless Sphynx are all certain to start a conversation.Coat — or lack of it — sets some breeds apart. Primary among these breeds is the Sphynx, a cat who’s nearly hairless — nothing more than a little fuzz on his face, feet, and tail. The Rex breeds — Cornish, Devon, German, and Selkirk — all sport kinky hair, as does the LaPerm and the American Wirehair.

Some breeders of Rexes claim an additional distinction for their breeds: They claim that the cats are hypoallergenic. Some people with allergies may be able to tolerate certain breeds more than others, true, but unfortunately, no such thing as a completely allergy-proof cat exists.

Tails—or lack thereof—are the talk in other breeds. The Manx is undoubtedly the best-known tailless or short-tailed cat, but others are on this list, too. The Cymric is a longhaired Manx; the Japanese Bobtail, American Bobtail, and Pixie-Bob round out the ranks of the tail-challenged.

And what about ears? Two breeds are based on an ear mutation: the Scottish Fold, with ears that fold forward, and the American Curl, with ears that arch backward.

Undoubtedly the most talked-about new breed has been the Munchkin, a cat with short legs. Although some people say that the breed is a mutation that shouldn’t be developed into an actual breed, others see little difference between having a short-legged cat breed and a short-legged dog breed, of which several exist. One thing is certain: The controversy over breeds developed from mutations isn’t about to abate anytime soon.

Should you consider any of these breeds? Of course. If you’re looking for something that’s sure to start a conversation whenever company comes over, these cats are just the ticket. But be prepared, too, to hear from those who think it’s a bad idea to perpetuate such genetic surprises.

The unCATegorizables

Herding cats is hard work, and some breeds refuse any efforts at being categorized. One, the Singapura, a Southeast Asian breed that resembles an Abyssinian, is noteworthy for being exceptionally small, which practically puts the breed in a category of its own.And where do you put the Snowshoe, a cat with many breeds in its background who resembles a white-mitted Siamese but isn’t as active? We couldn’t decide.

Three other breeds are of medium size and temperament but are notable for their coats. Count among these the Korat and Russian Blue, from Thailand and Russia, respectively, both remarkable for their stunning blue-gray coats—as is the Nebelung.