Suppose that one of your customers is a company that really values reliability. That company considers it important for a supplier to deliver exactly what was ordered, exactly the same way, every time. The culture of that group — the things that the company values — determines how it judges its suppliers. Now suppose that this customer has a choice of working with two suppliers: one that's known for consistent quality and another that's known for flexibility and innovation. Naturally, the first supplier would be a better cultural fit for this particular supply chain because of the value that the customer places on reliability.

The impact of culture can also apply to the functions within your organization. Different departments — such as purchasing, logistics, and operations — often develop cultures of their own. If the values of these departments clash, it's difficult for the company to manage its supply chain effectively.

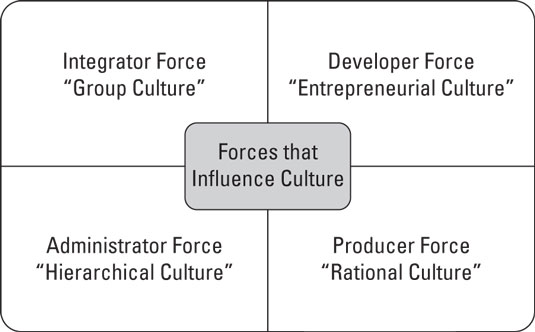

One useful way to think about the culture of a company or a department is to use a framework that was developed by professor and thought leader Dr. John Gattorna in Dynamic Supply Chains: Delivering Value through People, 2nd Edition (FT Press, 2010). Gattorna says that four major behavioral forces (see the following figure) determine the culture of a group. These forces are often related to the style of a group's leader and the norms for a particular industry.

- Integrator: Force for cohesion, cooperation, and relationships

- Developer: Force for creativity, change, and flexibility

- Administrator: Force for analysis, systems, and control

- Producer: Force for energy, action, and results

Dominant group personalities.

Dominant group personalities.The strength of these personality forces lead to differences in the culture for a team or organization. The most accurate way to measure culture is to formally interview people on a team and then analyze their responses. But in many cases, you can get a good sense for a team's culture simply by working with them for a little while.

Teams that are driven by the Integrator force tend to have a "group" culture, where everyone on the team is encouraged to develop personal relationships and informal communications. In a group culture, people feel like they are part of a family. But a group culture also tends to be exclusive — it's their team against everyone else.

Teams that are driven by the Developer force form an "entrepreneurial" culture, where everyone is focused on achieving a common vision. Communications are informal and ideas are exchanged with people inside and outside of the group. An entrepreneurial culture may tolerate "bad" behaviors, as long as they doesn't interfere with achieving the shared goal.

Teams that are driven by the Administrator force create a "hierarchical" culture, where communication is formal and shared through official channels. Hierarchical cultures are good at developing processes and ensuring consistency, but they're often slow and inflexible.

Teams that are driven by the Producer force develop a "rational" culture, where communications are concise and fast. Plans are made, plans are executed, and updates are sent out to keep stakeholders in the loop. Rational cultures are good at keeping teams focused and delivering results. But these cultures often find it hard to deviate from a plan, even when the circumstances around them change.

A useful exercise when analyzing your supply chain is to list the groups that work together, and try to determine the dominant culture for each of them. This can often help you anticipate conflicts that can emerge when these groups interact. And, it can help you find ways to use these differences to your advantage. Here are some common examples that illustrate how this can work:

- Purchasing departments often have an hierarchical culture whereas operations departments have a rational culture. In this situation, the purchasing department may feel frustrated because operations doesn't follow the rules. Operations may be frustrated because purchasing is slowing them down. So you could create a small team of expeditors, with members from both operations and purchasing, to manage urgent orders while assuring that all of the proper policies are followed.

- Large companies often have strict rules that lead to a hierarchical culture. Technology companies that focus on innovation have an entrepreneurial culture. In order for big bureaucracies to take advantage of the latest technologies, they may need to start new programs that respond faster and have more flexibility for their suppliers.

- Human resources teams often have an group culture, whereas consultants may have a rational culture. The human resources team may find the consultants to be rude and disinterested, and the consultants may view the human resources team as nosey and unprofessional. In order for these groups to work effectively through a corporate merger, for example, you may need to schedule time for them to interact in a social setting such as a kickoff celebration.

Gattorna makes the point that supply chains are dynamic, so balancing these forces is an ongoing process. One way to create balance is to build teams of people with each of these tendencies. If the team has a diverse set of personalities, the team is more likely to appreciate the strengths of diverse supply chain partners and to find ways to build effective relationships with other teams that emphasize any one of the forces.