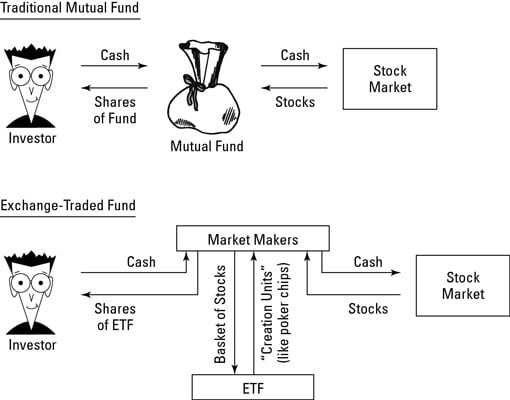

The structure of exchange-traded funds (ETFs) makes them different than mutual funds. Actually, ETFs are legally structured in three different ways: as exchange-traded open-end mutual funds, exchange-traded unit investment trusts, and exchange-traded grantor trusts. The differences are subtle.

One seminal difference between ETFs and mutual funds is basically an extremely clever setup whereby ETF shares, which represent stock holdings, can be traded without any actual trading of stocks.

In the world of ETFs, there are no croupiers, but there are market makers. Market makers are people who work at the stock exchanges and create (like magic!) ETF shares.

Each ETF share represents a portion of a portfolio of stocks, sort of like poker chips represent a pile of cash. As an ETF grows, so does the number of shares. Concurrently (once a day), new stocks are added to a portfolio that mirrors the ETF.

When an ETF investor sells shares, those shares are bought by a market maker who turns around and sells them to another ETF investor.

By contrast, with mutual funds, if one person sells, the mutual fund must sell off shares of the underlying stock to pay off the shareholder. If stocks sold in the mutual fund are being sold for more than the original purchase price, the shareholders left behind are stuck paying a capital gains tax. In some years, that amount can be substantial.

In the world of ETFs, no such thing has happened or is likely to happen, at least not with the vast majority of ETFs, which are index funds. Because index funds trade infrequently, and because of ETFs’ poker-chip structure, ETF investors rarely see a bill from Uncle Sam for any capital gains tax.

That’s not a guarantee that there will never be capital gains on any index ETF, but if there ever are, they are sure to be minor.

The actively managed ETFs — currently a very small fraction of the ETF market, but almost certain to grow — may present a somewhat different story. They are going to be, no doubt, less tax friendly than index ETFs but more tax friendly than actively managed mutual funds.

Tax efficient does not mean tax-free. Although you won’t pay capital gains taxes, you will pay taxes on any dividends issued by your stock ETFs, and stock ETFs are just as likely to issue dividends as are mutual funds.

In addition, if you sell your ETFs and they are in a taxable account, you have to pay capital gains tax (15 percent for most folks; 20 percent after 2012) if the ETFs have appreciated in value since the time you bought them. But hey — at least you get to decide when to take a gain, and when you do, it’s an actual gain.

ETFs that invest in taxable bonds and throw off taxable bond interest are not likely to be very much more tax friendly than taxable-bond mutual funds.

ETFs that invest in actual commodities, holding real silver or gold, tax you at the “collectible” rate of 28 percent. And ETFs that tap into derivatives (such as commodity futures) and currencies sometimes bring with them very complex (and costly) tax issues.

Taxes on earnings — be they dividends or interest or money made on currency swaps — aren’t an issue if your money is held in a tax-advantaged account, such as a Roth IRA.