But the main reason that the name is used in Python is because the term lambda is used to describe anonymous functions in calculus. Now that we’ve cleared that up, you can use this info to spark enthralling conversation at office parties.

The minimal syntax for defining a lambda expression (with no name) with Python is:

Lambda arguments : expressionWhen using it:

- Replace

argumentswith data being passed into the expression. - Replace

expressionwith an expression (formula) that defines what you want the lambda to return.

Adams, Ma, diMeola, ZanduskySuppose you write the following code to put the names into a list, sort it, and then print the list, like this:

names = ['Adams', 'Ma', 'diMeola', 'Zandusky'] names.sort() print(names)That output from this is:

['Adams', 'Ma', 'Zandusky', 'diMeola']Having diMeola come after Zandusky seems wrong to some beginners. But computers don’t always see things the way we do. (Actually, they don’t “see” anything because they don’t have eyes or brains … but that’s beside the point.) The reason diMeola comes after Zandusky is because the sort is based on ASCII, which is a system in which each character is represented by a number.

All the lowercase letters have numbers that are higher than uppercase numbers. So, when sorting, all the words starting with lowercase letters come after the words that start with an uppercase letter. If nothing else, it at least warrants a minor hmm.

To help with these matters, the Python sort() method lets you include a key= expression inside the parentheses, where you can tell it how to sort. The syntax is:

.sort(key = transform)The

transform part is some variation on the data being sorted. If you're lucky and one of the built-in functions like len (for length) will work for you, then you can just use that in place of transform, like this:

names.sort(key=len)Unfortunately for us, the length of the string doesn't help with alphabetizing. So when you run that, the order turns out to be:

['Ma', 'Adams', 'diMeola', 'Zandusky']The sort is going from the shortest string (the one with the fewest characters) to the longest string. Not helpful at the moment.

You can’t write key=lower or key=upper to base the sort on all lowercase or all uppercase letters either, because lower and upper aren't built-in functions (which you can verify pretty quickly by googling python 3.7 built-in functions).

In lieu of a built-in function, you can use a custom function that you define yourself using def. For example, you can create a function named lower() that accepts a string and returns that string with all of its letters converted to lowercase. Here is the function:

def lower(anystring): """ Converts string to all lowercase """ return anystring.lower()The name

lower is made up, and anystring is a placeholder for whatever string you pass to it in the future. The return anystring.lower() returns that string converted to all lowercase using the .lower() method of the str (string) object. (Read about Python string methods for more information.)You can't use key=lower in the sort() parentheses because lower() isn't a built-in function. It’s a method … not the same. Kind of annoying with all these buzzwords.

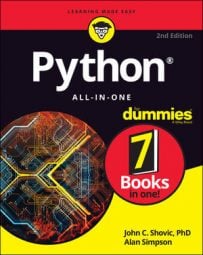

Suppose you write this function in a Jupyter cell or .py file. Then you call the function with something like print(lowercaseof('Zandusky')). What you get as output is that string converted to all lowercase, as you see below.

Putting a custom function named lower() to the test.

Putting a custom function named lower() to the test.

Okay, so now you have a custom function to convert any string to all lowercase letters. How do you use that as a sort key? Easy, use key=transform the same as before, but replace transform with your custom function name. The function is named lowercaseof.sort(key= lowercaseof), as shown in the following:

def lowercaseof(anystring): """ Converts string to all lowercase """ return anystring.lower() names = ['Adams', 'Ma', 'diMeola', 'Zandusky'] names.sort(key=lowercaseof)Running this code to display the list of names puts them in the correct order, because it based the sort on strings that are all lowercase. The output is the same as before because only the sorting, which took place behind the scenes, used lowercase letters. The original data is still in its original uppercase and lowercase letters.

'Adams', 'diMeola', 'Ma', 'Zandusky'If you’re still awake and conscious after reading all of this you may be thinking, “Okay, you solved the sorting problem. But I thought we were talking about lambda functions here. Where’s the lambda function?” There is no lambda function yet.

But this is a perfect example of where you could use a lambda function, because the Python function you’re calling, lowercaseof(), does all of its work with just one line of code: return anystring.lower().

When your function can do its thing with a simple one-line expression like that, you can skip the def and the function name and just use this syntax:

lambda parameters : expressionReplace

parameters with one or more parameter names that you make up yourself (the names inside the parentheses after def and the function name in a regular function). Replace expression with what you want the function to return without the word return. So in this example the key, using a lambda expression, would be:

lambda anystring : anystring.lower()Now you can see why it's an anonymous function. The whole first line with function name

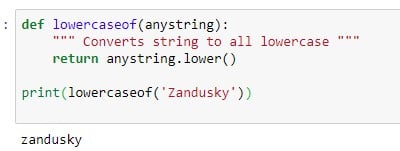

lowercaseof() has been removed. So the advantage of using the lambda expression is that you don’t even need the external custom function at all. You just need the parameter followed by a colon and an expression that tells it what to return.The image below shows the complete code and the result of running it. You get the proper sort order without the need for a customer external function like lowercaseof(). You just use anystring : anystring.lower() (after the word lambda) as the sort key.

Using a lambda expression as a sort key.

Using a lambda expression as a sort key.

Let’s also add that anystring is a longer parameter name than most Pythonistas would use. Python folks are fond of short names, even single-letter names. For example, you could replace anystring with s (or any other letter), as in the following, and the code will work exactly the same:

names = ['Adams', 'Ma', 'diMeola', 'Zandusky'] names.sort(key=lambda s: s.lower()) print(names)Way back at the beginning of this tirade, it was mentioned that a

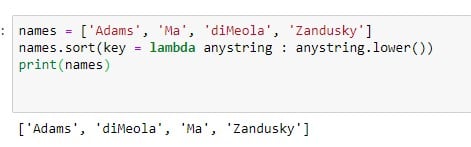

lambda function doesn't have to be anonymous. You can give them names and call them as you would other functions.For example, here is a lambda function named currency that takes any number and returns a string in currency format (that is, with a leading dollar sign, commas between thousands, and two digits for pennies):

currency = lambda n : f"${n:,.2f}"

Here is one named percent that multiplies any number you send to it by 100 and shows it with two a percent sign at the end:

percent = lambda n : f"{n:.2%}"

The following image shows examples of both functions defined at the top of a Jupyter cell. Then a few print statements call the functions by name and pass some sample data to them. Each print() statements displays the number in the desired format. Two functions for formatting numbers.

Two functions for formatting numbers.

The reason you can define those as single-line lambdas is because you can do all the work in one line, f"${n:,.2f}" for the first one and f"{n:.2%}" for the second one. But just because you can do it that way, doesn't mean you must. You could use regular functions too, as follows:

# Show number in currency format.

def currency(n):

return f"${n:,.2f}"

def percent(n):

# Show number in percent format.

return f"{n:.2%}"

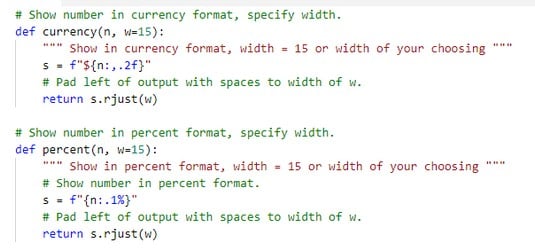

With this longer syntax, you could pass in more information too. For example, you may default to a right-aligned format within a certain width (say 15 characters) so all numbers came out right-aligned to the same width. The image shows this variation on the two functions. Two functions for formatting numbers with fixed width.

Two functions for formatting numbers with fixed width.

In the image above, the second parameter is optional and defaults to 15 if omitted. So if you call it like this:

print(currency(9999))… you get $9,999.00 padding with enough spaces on the left to make it 15 characters wide. If you call it like this instead:

print(currency(9999,20)… you still get $9,999.00 but padded with enough spaces on the left to make it 20 characters wide.

The .ljust() used above is a Python built-in string method that pads the left side of a string with sufficient spaces to make it the specified width. There’s also an rjust() method to pad the right side. You can also specify a character other than a space. Google python 3 ljust rjust if you need more info.

So there you have it, the ability to create your own custom functions in Python. In real life, what you want to do is, any time you find that you need access to the same chunk of code — the same bit of login — over and over again in your app, don’t simply copy/paste that chunk of code over and over again. Instead, put all that code in a function that you can call by name.

That way, if you decide to change the Python stringcode, you don’t have to go digging through your app to find all the places that need changing. Just change it in the function where it’s all defined in one place.