Today, the remains of Greek cities can be found in Italy, Sicily, and Turkey. One of the reasons that they have lasted so long is that the Greeks built their temples, amphitheaters, and other major public buildings with limestone and marble. Blocks of stone were held in place by bronze or iron pins set into molten lead — a flexible system that could withstand earthquakes.

Greek architecture followed a highly structured system of proportions that relates individual architectural components to the whole building. This system was developed according to three styles, or orders.

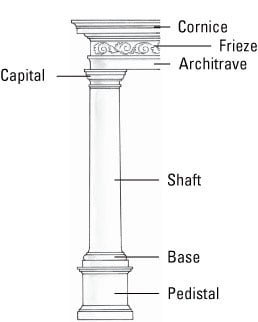

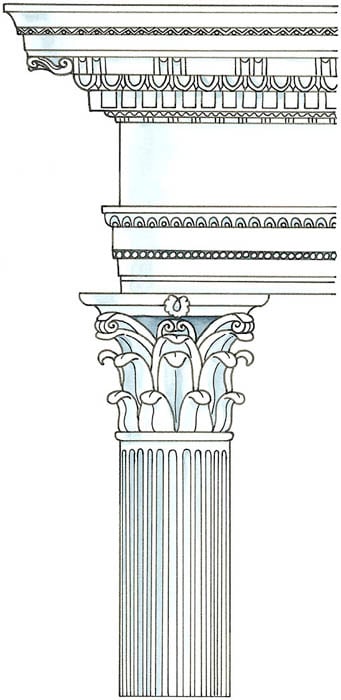

Each of the orders consists of an upright support called a column that extends from a base at the bottom to a shaft in the middle and a capital at the top — much like the feet, body, and head of the human figure. The capital was often a stylized representation of natural forms, such as animal horns or plant leaves. It, in turn, supports a horizontal element called the entablature, which is divided further into three different parts:

- The architrave (lowest part)

- The frieze (middle)

- The cornice (top)

The Greeks started out using only one order per building. But after a few hundred years, they got more creative and sometimes used one order for the exterior and another for the interior. The proportions of the orders were developed over a long period of time — they became lighter and more refined.

Some folks think that the orders are primarily a question of details, moldings, and characteristic capitals. However, in fact, the very concept of order and an overall relationship is really the most important thing here. Each of the orders is a proportional system or a range of proportions for the entire structure.

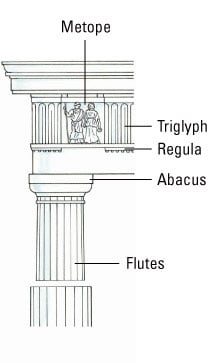

Doric: Heavy simplicity

The oldest, simplest, and most massive of the three Greek orders is the Doric, which was applied to temples beginning in the 7th century B.C. As shown in Figure 2, columns are placed close together and are often without bases. Their shafts are sculpted with concave curves called flutes. The capitals are plain with a rounded section at the bottom, known as the echinus, and a square at the top, called the abacus. The entablature has a distinctive frieze decorated with vertical channels, or triglyphs. In between the triglyphs are spaces, called metopes, which were commonly sculpted with figures and ornamentation. The frieze is separated from the architrave by a narrow band called the regula. Together, these elements formed a rectangular structure surrounded by a double row of columns that conveyed a bold unity. The Doric order reached its pinnacle of perfection in the Parthenon.

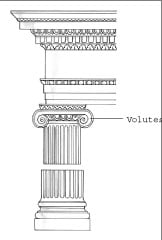

Ionic: Look for the two scrolls

The next order to be developed by the Greeks was the Ionic (see Figure 3). It is called Ionic because it developed in the Ionian islands in the 6th century B.C. Roman historian Vitruvius compared this delicate order to a female form, in contrast to the stockier "male" Doric order.The Ionic was used for smaller buildings and interiors. It's easy to recognize because of the two scrolls, called volutes, on its capital. The volutes may have been based on nautilus shells or animal horns.

Between the volutes is a curved section that is often carved with oval decorations known as egg and dart. Above the capital, the entablature is narrower than the Doric, with a frieze containing a continuous band of sculpture. One of the earliest and most striking examples of the Ionic order is the tiny Temple to Athena Nike at the entrance to the Athens Acropolis. It was designed and built by Callicrates from about 448-421 B.C.

Corinthian: Leafy but not as popular

The third order is the Corinthian, which wasn't used much by the Greeks. It is named after the city of Corinth, where sculptor Callimachus supposedly invented it by at the end of the 5th century B.C. after he spotted a goblet surrounded by leaves. As shown in Figure 4, the Corinthian is similar to the Ionic order in its base, column, and entablature, but its capital is far more ornate, carved with two tiers of curly acanthus leaves. The oldest known Corinthian column stands inside the 5th-century temple of Apollo Epicurius at Bassae.

Compensating for illusions: Straight or curved, who knew?

The Greeks continued to strive for perfection in the appearance of their buildings. To make their columns look straight, they bowed them slightly outward to compensate for the optical illusion that makes vertical lines look curved from a distance. They named this effect entasis, which means "to strain" in Greek.

Relationships between columns, windows, doorways, and other elements were constantly analyzed to find pleasing dimensions that were in harmony with nature and the human body. Symmetry and the unity of parts to the whole were important to Greek architecture, as these elements reflected the democratic city-state pioneered by the Greek civilization.