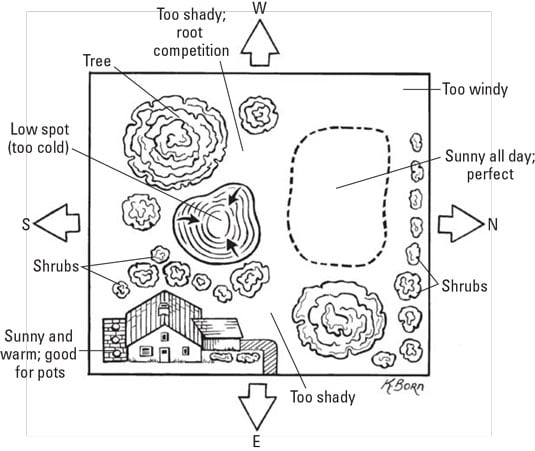

When considering where to plop down your homestead's garden plot, think of these three main elements, which are necessary for the perfect spot: site, sun, and soil.

Illustration by Kathryn Born

Illustration by Kathryn BornA sample yard with possible (and impossible) sites for a vegetable garden.

Don’t be discouraged if you lack the ideal garden spot — few gardeners have one. Just try to make the most of what you have.

Homesteading and your weather conditions

The first step in planting wisely is understanding your region’s climate, as well as your landscape’s particular attributes. Then you can effectively match plants to planting sites.Don’t use geographic proximity alone to evaluate climate. Two places near each other geographically can have very different climates if one is high on a mountainside and the other is on the valley floor, for example. Also, widely separated regions can have similar climates.

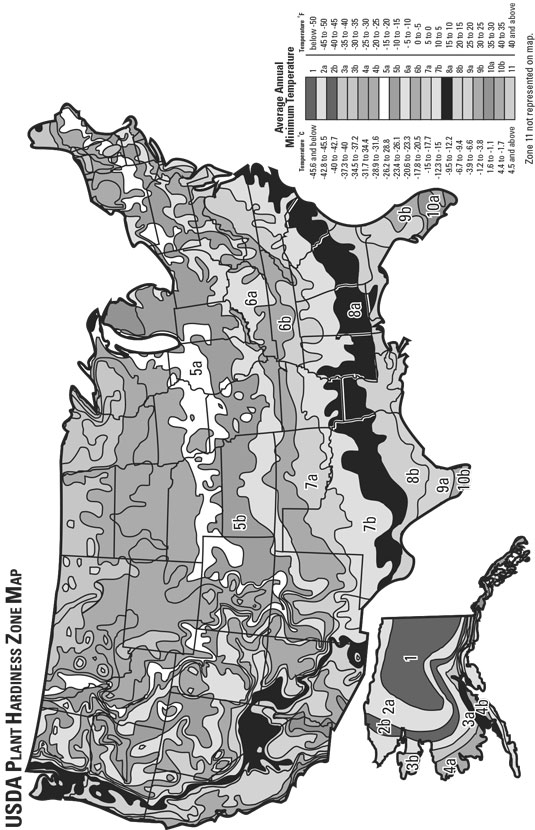

USDA Plant Hardiness Zone Map

Low winter temperatures limit where most plants will grow. After compiling weather data collected over many years, the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) divided North America, Europe, and China into 11 zones. Each zone represents an expected average annual minimum temperature.On the USDA Plant Hardiness Zone Map for North America (see the following figure), each of the 11 zones is 10°F warmer or colder in an average winter than the adjacent zone. The warmest zone, Zone 11, records an average low annual temperature of 40°F or higher. In Zone 1, the lowest average annual temperature drops to minus 50°F or colder. Brrr!

The USDA Plant Hardiness Zone Map indicates each zone’s expected average annual minimum temperature.

The USDA Plant Hardiness Zone Map indicates each zone’s expected average annual minimum temperature.Zones 2 through 10 on some North American maps are further subdivided into a and b regions. The lowest average annual temperature in Zone 5a, for example, is 5°F warmer than the temperature in Zone 5b. When choosing plants that are just barely hardy in your zone, knowing whether your garden falls into the a or b category can ease your decision. After a few years of personal weather observation in your own garden, you’ll have a pretty clear idea of what to expect for winter low temperatures too.

Most books, catalogs, magazines, and plant labels use the USDA zone system. For a color version, which may be a bit easier to read, visit the U.S. National Arboretum website, which offers a map of North America and individual regions.

The USDA map is based on a single factor: a region’s average minimum winter temperature. Many other factors affect a plant’s ability to thrive in a particular environment, so use the map only as a guideline.

AHS Heat Zone Map

To help gardeners in warm climates, the American Horticultural Society developed the AHS Heat Zone Map. This map divides the United States into 12 zones based on the average number of heat days each year — days that reach temperatures of 86°F or higher. Zone 1 has fewer than one heat day per year; Zone 12 has more than 210.Order your own color poster of the AHS Heat Zone Map by calling the society at (800) 777-7931, ext. 137. Or visit the American Horticulture Society’s website for more information and a downloadable map. The site also offers a Heat Zone Finder to locate your particular heat zone by zip code.

Sunset map

In an attempt to take total climate into consideration when evaluating plant hardiness, Sunset Publishing created Sunset’s Garden Climate Zones, a map that divides the country into 24 zones. This map is especially useful to gardeners in the western United States, where mountains, deserts, and coastal areas create wildly diverse climates, sometimes within a few miles of each other.Although most national plant suppliers and references use the USDA zone map, regional garden centers and growers in the western half of the country often refer to the Sunset map.

Factor microclimates into your homestead gardening

Within larger climates, smaller pockets exist that differ somewhat from the prevailing weather around them. These microclimates occur wherever a building, body of water, dense shrubs, or hillside modifies the larger climate.Microclimates may be very small, such as the sunny side of your house or the shady side under a tree, or as large as a village. A town on the shore of Lake Michigan has a different microclimate than a town just 20 miles inland, for example. Common microclimates around your property may include the following:

- North side of the house: Cool and shady year-round

- South side of the house: Hot and sunny all day; often dry

- East side of the house: Warm morning sun and cool afternoon shade

- West side of the house: Morning shade and hot afternoon sun

- Top of a hill: Exposed to wind and sun; soil dries quickly

- Bottom of a hill: Collects cold air and may be poorly drained due to precipitation that runs down the slope

Plan your landscape and gardens to take advantage of microclimates. Use wind-sheltered areas to protect tender plants from drying winter winds in cold climates and hot, dry winds in arid places. Put plants such as phlox and lilac, which are prone to leaf disease, in breezy garden spots as a natural way to prevent infections. Avoid putting frost-tender plants at the bottoms of hills, where pockets of cold air form.

Urban environments typically experience higher temperatures than suburban or rural areas thanks to so many massive heat absorbers such as roofs, steel and glass buildings, concrete, billboards, and asphalt-paved surfaces. And that doesn’t even begin to account for all the waste heat generated by human sources such as cars, air conditioners, and factories. The urban homesteader needs to consider all of these additional factors that could make their microclimate even more of a challenge.

How to choose a homestead garden site

Choosing a site is the important first step in planning a vegetable garden. This may sound like a tough choice to make, but don’t worry; a lot of the decision is based on good old common sense. When you’re considering a site for your garden, remember these considerations:- Keep it close to home. Plant your garden where you’ll walk by it daily so that you remember to care for it. Also, a vegetable garden is a place people like to gather, so keep it close to a pathway.

Vegetable gardens used to be relegated to some forlorn location out back. Unfortunately, if it’s out of sight, it’s out of mind. But most homesteaders prefer to plant vegetables front and center — even in the front yard. That way you get to see the fruits of your labor and remember what chores need to be done. Plus, it’s a great way to engage the neighbors as they stroll by and admire your plants. You may even be inspired to share a tomato with them.

- Make it easy to access. If you need to bring in soil, compost, mulch, or wood by truck or car, make sure your garden can be easily reached by a vehicle. Otherwise you’ll end up working way too hard to cart these essentials from one end of the yard to the other.

- Have a water source close by. Try to locate your garden as close as you can to an outdoor faucet. Hauling hundreds of feet of hose around the yard to water the garden will cause only more work and frustration. And, hey, isn’t gardening supposed to be fun?

- Keep it flat. You can garden on a slight slope, and, in fact, a south-facing one is ideal since it warms up faster in spring. However, too severe a slope could lead to erosion problems. To avoid having to build terraces like those at Machu Picchu, plant your garden on flat ground.

How big is too big for a veggie garden? If you’re a first-time gardener, a size of 100 square feet is plenty of space to take care of. However, if you want to produce food for storing and sharing, a 20-foot-by-30-foot plot (600 square feet) is a great size. You can produce an abundance of different vegetables and still keep the plot looking good.

Speaking of upkeep, keep the following in mind when deciding how large to make your garden: If the soil is in good condition, a novice gardener can keep up with a 600-square-foot garden by devoting about a half-hour each day the first month of the season; in late spring through summer, a good half-hour of work every two to three days should keep the garden productive and looking good. Keep in mind that the smaller the garden, the less time it’ll take to keep it looking great. Plus, after it’s established, the garden will take less time to get up and running in the spring.Let the sun shine on your homestead garden plot

Vegetables need enough sun to produce at their best. Fruiting vegetables, such as tomatoes, peppers, beans, squash, melons, cucumbers, and eggplant, need at least six hours of direct sun a day for good yields. The amount of sun doesn’t have to be continuous though. You can have three hours in the morning with some shade midday and then three more hours in the late afternoon.

However, if your little piece of heaven gets less than six hours of sun, don’t give up. You have some options:- Crops where you eat the leaves, such as lettuce, arugula, pac choi, and spinach, produce reasonably well in a partially shaded location where the sun shines directly on the plants for three to four hours a day.

- Root crops such as carrots, potatoes, and beets need more light than leafy vegetables, but they may do well getting only four to six hours of sun a day.

If you don’t have enough sun to grow all the fruiting crops that you want, such as tomatoes and peppers, consider supplementing with a movable garden. Plant some crops in containers and move them to the sunniest spots in your yard throughout the year.

Keep in mind that sun and shade patterns change with the seasons. A site that’s sunny in midsummer may later be shaded by trees, buildings, and the longer shadows of late fall and early spring. If you live in a mild-winter climate, such as parts of the southeastern and southwestern United States where it’s possible to grow vegetables nearly year-round, choosing a spot that’s sunny in winter as well as in summer is important. In general, sites that have clear southern exposure are sunniest in winter.You can have multiple vegetable garden plots around your yard matching the conditions with the vegetables you’re growing. If your only sunny spot is a strip of ground along the front of the house, plant a row of peppers and tomatoes. If you have a perfect location near a backdoor, but it gets only morning sun, plant lettuce and greens in that plot.

If shade in your garden comes from nearby trees and shrubs, your vegetable plants will compete for water and nutrients as well as for light. Tree roots extend slightly beyond the drip line, the outer foliage reach of the tree. If possible, keep your garden out of the root zones (the areas that extend from the drip lines to the trunks) of surrounding trees and shrubs. If avoiding root zones isn’t possible, give the vegetables more water and be sure to fertilize to compensate.

How to test your soil’s drainage

After you’ve checked the site location and sun levels of your prospective garden, you need to focus on the third element of the big three: the soil. Ideally you have rich, loamy, well-drained soil. Unfortunately, that type of soil is a rarity. But a key that’s even more essential to good soil is proper water drainage. Plant roots need air as well as water, and water-logged soils are low in air content. Puddles of water on the soil surface after a rain indicate poor drainage.One way to check your soil’s drainage is to dig a hole about 10 inches deep and fill it with water. Let the water drain and then fill the hole again the following day. Time how long it takes for the water to drain away. If water remains in the hole more than 8 to 10 hours after the second filling, your soil drainage needs improvement.

Soils made primarily of clay tend to be considered heavy. Heavy soils usually aren’t as well drained as sandy soils. Adding lots of organic matter to your soil can improve soil drainage. Or you also can build raised beds on a poorly drained site.But slow water drainage isn’t always a bad thing. Soil also can be too well drained. Very sandy soil dries out quickly and needs frequent watering during dry spells. Again, adding lots of organic matter to sandy soil increases the amount of water it can hold.

If you encounter a lot of big rocks in your soil, you may want to look for another spot. Or consider going the raised-bed route. You can improve soils that have a lot of clay or that are too sandy, but very rocky soil can be a real headache. In fact, it can be impossible to garden in.

Don’t plant your garden near or on top of the leach lines of a septic system, for obvious reasons. And keep away from underground utilities. If you have questions, call your local utility company to locate underground lines. If you’re unsure what’s below ground, visit Call 811 to have lines or pipes identified for free.