The study of genetics and inheritance is a big topic. Huge, really. What follows are some basic tenets relevant to queen-rearing and bee breeding. Just like people, chickens, and peas, genes determine the particulars of appearance and capabilities of your bees.

In bees, there are genes that control body color, disease resistance, and temperament, and these traits are passed from one generation to the next. Which body color, what type and level of disease resistance, gentle or cranky . . . the possible outcomes for the offspring are limited to the genes carried by the parents. Honey bees are responsive to selection, and in just a few seasons you can influence the overall health of your colonies.

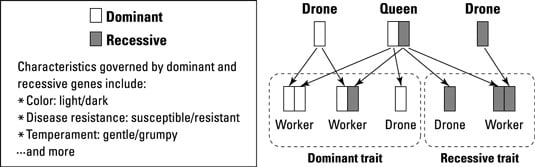

All queens and workers develop from fertilized eggs. They possess a full set of chromosomes and have a complete genetic makeup (a mother and father). Drones develop from unfertilized eggs and have half the full set of chromosomes (a mother, but no father). If an individual winds up with two different genes for color, the dominant color will be expressed.

Dominant and recessive genes

In honey bees, the females are diploid, meaning they possess two sets of genes — one from their father and one from their mother. If they receive a different gene from each parent, the dominant gene will be expressed and the recessive won’t be evident.

When the queen’s ovaries produce eggs, the genes are divided in half. If a queen’s body-color gene pair are the same, she will exhibit that color. If they are different, she will exhibit the dominant color. Half of her eggs receive the dominant color gene, whereas the other half of her eggs carry the gene for the recessive color.

If that egg is fertilized — if it goes on to become a female, not a male — then the ensuing larva will have two genes for color. If the two genes match, then that is the color the bee will be. If they are different, then again, she will show the dominant color and carry the gene for the recessive color . . . sort of in secret.

So as you get into queen rearing, you use the very best queen or queens in your operation as queen mothers and encourage other colonies with desirable traits to produce drones.

As you raise successive generations of queens, you can begin to select queens to continue the improvement process. In just a few seasons, it is possible to have a substantial influence on the nature of your bees, whether it be color, temperament, or disease resistance.

If you wind up with more queens than you can use, get them to good homes. You can select the very best to keep for your own colonies, and from those you can select your next queen mother and drone mothers. But the other queens are fine queens, too, so no harm in selling (or giving) them to fellow beekeepers.

Be sure to ask for feedback from these customers — get their impression of the health and character of the queens you’ve raised, and make notes so you can continually improve the genetics.

Inbreeding versus outcrossing

Imagine if you had a truly isolated mating yard, and you selected certain traits over many generations. The gene pool of your breeding stock would become more and more focused, with less variation, and would yield more consistent bees with most or all having the traits for which you’ve selected. But beyond a certain point, that genetic focus can become a liability, and inbreeding can occur. Inbreeding in honeybees is evidenced by a scattered brood pattern.

Rather than the nice, continuous expanse of capped worker brood, there are many skipped cells caused by the queen mating with too many drones that are too closely related to her. The workers can tell this inbreeding, and they remove the inbred larva, leaving skips in the brood pattern. A skip here and there is normal, but in inbred bees the skips become much more prevalent.

But for the small-scale queen rearer and bee breeder, this is not likely to happen. Truly isolated mating areas are rare, and it’s very likely that even though you stack the deck, there will be incursions from other bee stock. Bees from neighboring beekeepers or from feral colonies will mix with your stock enough to avoid inbreeding.

If you believe you have a fairly isolated mating area, you may want to deliberately introduce some unrelated bees to your operation from time to time. Bees from different sources, different races, and so forth bring some diversity to your stock. This counteracts any possible inbreeding with a dose of outcrossing and keeps the genetic diversity from becoming too limited.