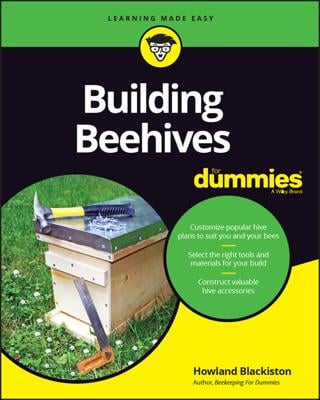

You can keep bees just about anywhere: in the countryside, in the city, in a corner of the garden, by the back door, in a field, on the terrace, or even on a rooftop downtown. You don't need a great deal of space, nor do you need to have flowers on your property. Bees will happily travel for miles to forage for what they need. These girls are amazingly adaptable, but you'll get optimum results and a more rewarding honey harvest if you follow some basic guidelines (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: The picture-perfect beeyard.

Basically, you're looking for easy access (so you can tend to your hives), good drainage (so the bees don't get wet), a nearby water source for the bees, dappled sunlight, and minimal wind. Keep in mind that fulfilling all these criteria may not be possible. Do the best you can by:

- Facing your hive to the southeast. That way your bees get an early morning wake-up call and start foraging early.

- Positioning your hive so that it is easily accessible come honey harvest time. You don't want to be hauling hundreds of pounds of honey up a hill on a hot August day.

- Providing a windbreak at the rear of the hive. You could do this by planting a few hemlocks behind your hives, for example. Or you can erect a fence made from posts and burlap, blocking harsh winter winds that can stress the colony.

- Putting the hive in dappling sunlight. Ideally, avoid full sun, because the warmth of the sun requires the colony to work hard to regulate the hive's temperature in the summer. By contrast, you also want to avoid deep, dark shade, because it can make the hive damp and the colony listless.

- Making sure the hive has good ventilation. Avoid placing it in a gully where the air is still and damp. Also, avoid putting it at the peak of a hill, where bees are subject to winter's fury.

- Placing the hive absolutely level from side to side, and with the front of the hive just slightly lower than the rear (a difference of an inch or less is fine), so that any rainwater drains out of the hive (and not into it).

- Locating your hive on firm, dry land. Don't let it sink into the quagmire.

- Mulch around the hive prevents grass and weeds from blocking its entrances.

Providing for your thirsty bees

During their foraging season, bees collect more than just nectar and pollen. They gather a whole lot of water. They use it to dilute honey that's too thick, and to cool the hive during hot weather. Field bees bring water back to the hive and deposit it in cells, while other bees fan their wings furiously to evaporate the water and regulate the temperature of the hive.

If your hive is at the edge of a stream or pond, that's perfect. But if it isn't, you should provide a nearby water source for the bees. Keep in mind that they'll seek out the nearest water source. You certainly don't want that to be your neighbor's kiddy pool. You can improvise all kinds of watering devices. Figure 2 shows an attractive and natural-looking watering device situated on top of a boulder that sits in one beeyard. All it took was a little cement, a dozen rocks and a few minutes of amateur masonry skills.

Figure 2: A shallow bee watering pool constructed on a boulder near the hives.

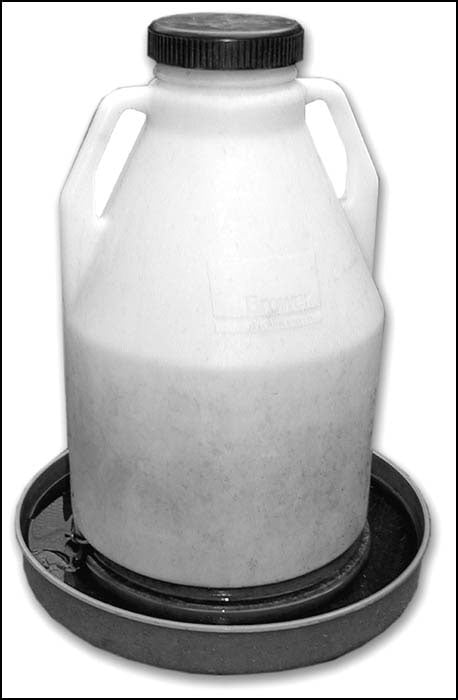

Consider these other watering options: a pie pan filled with gravel and topped off with water, a chicken-watering device (available at farm supply stores; see Figure 3), or simply an outdoor faucet that is encouraged to develop a slow drip.

Figure 3: A chicken waterer is a great way to provide your bees with water. Place some gravel or small pebbles in the tray, so the bees don't drown.

Understanding the correlation between geographical area and honey flavors

The type of honey you eat usually is classified by the primary floral sources from which the bees gathered the nectar. A colony hived in the midst of a huge orange grove collects nectar from the orange blossoms — thus the bees make orange-blossom honey. Bees in a field of clover make clover honey, and so on. As many different kinds of honey can exist as there are flowers that bloom. The list gets long.

For most hobbyists, the flavor of honey they harvest depends upon the dominant floral sources in their areas. During the course of a season, your bees visit many different floral sources. They bring in many different kinds of nectar. The resulting honey, therefore, can properly be classified as wildflower honey, a natural blend of various floral sources.

The beekeeper who is determined to harvest a particular kind of honey (clover, blueberry, apple blossom, sage, tupelo, buckwheat, and so on) needs to locate his or her colony in the midst of acres of this preferred source and must harvest the honey as soon as that desired bloom is over. But, doing so is not very practical for the backyard beekeeper. That's what the commercial beekeepers do.

As a beginner, let the bees do their thing and collect from myriad nectar sources. You'll not be disappointed in the resulting harvest, because it will be unique to your neighborhood and better than anything you have ever tasted from the supermarket.