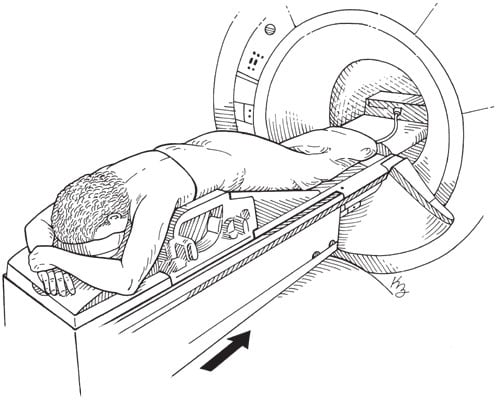

MRI has been used to find some breast cancers not seen on mammogram, but it is most likely to find a change in the breast that is not cancer (a false positive). To ensure that you verify the false-positive findings, you must do more tests and/or biopsies for resolution. This is why MRI is not normally recommended as a screening test for women at average risk of breast cancer, because it often means unneeded biopsies and other tests for many of these women. The figure illustrates a breast MRI procedure.

Illustration by Kathryn Born

Illustration by Kathryn BornBreast MRI procedure.

A breast MRI is often used for screening of women who have a high risk for breastcancer or who have a known breast cancer gene mutation (such as BRCA1 or BRCA 2).

Breast MRI is also used after a breast biopsy returns a positive result for cancer and you are considering a lumpectomy. The breast MRI will show if there are additional cancers, if your cancer has extended or involves a larger area of the breast, and if there are additional cancers or in another location of the same breast or the other (contralateral) breast.

Ultrasound, sometimes called sonography, is an imaging technique that uses high-frequency sound waves that pass into the breast and bounce back from the breast tissue to form an image of the breast. You've probably at least seen ultrasounds done on TV and in movies with pregnant women. It involves the use of a small probe (transducer) on the skin that is lubricated with gel, and the sound waves form an image on the computer screen. Ultrasound is not a first-line screening tool for breast cancer, but it can be a helpful tool to examine masses that have been felt in the breast.

Ultrasound is harmless and doesn't use ionizing radiation. It's often used to diagnose breast abnormalities that may or may not be detected by physical exam, including the following:

- Breast lump (benign or cancerous)

- Bloody or spontaneous clear nipple discharge

- Breast abscess

Ultrasound is also used to examine the axillary lymph nodes or armpit lymph nodes for changes that may signify that an active disease is present in the breast or under the armpit. The axillary lymph nodes can become swollen if you cut your arm while shaving, develop an abscess or infection in the breast or armpit, or develop a breast cancer or lymphoma.

Ultrasound is also used to evaluate dense breasts. When a breast is dense with fibrous and glandular tissue, identifying a breast cancer on a mammogram can be more difficult — both dense breast tissue and breast cancer appear white on a mammogram. Ultrasound of the breast is also used to examine a breast mass in a pregnant woman, because a mammogram during pregnancy isn't recommended (due to exposure of radiation during imaging).

Using breast ultrasound as an addition to a screening mammogram has its pros and cons. The pros are that it provides a full examination of the breast and it can determine the type of breast mass, which ultimately can help to provide you with a diagnosis. The cons are that the ultrasound may show abnormal changes that were not seen on the mammogram, and multiple biopsies may be required — with a final diagnosis that is negative for breast cancer.

All in all, it is better to be safe. Ask yourself: What are you willing to do to ensure your breast health?

If you have concerns about additional screening with breast ultrasound, you should discuss with your doctor to determine if it is right for you.