Email hacking: Attachments

An attacker can perform an email hack by creating an attachment-overload attack by sending hundreds or thousands of emails with very large attachments to one or more recipients on your network.Attacks using email attachments

Attachment attacks have a couple of goals:- The email server may be targeted for a complete interruption of service with these failures:

- Storage overload: Multiple large messages can quickly fill the total storage capacity of an email server. If the messages aren’t automatically deleted by the server or manually deleted by individual user accounts, the server will be unable to receive new messages.

This attack can create a significant DoS problem for your email system, either crashing it or requiring you to take your system offline to clean up the junk that has accumulated. A 100MB file attachment sent 10 times to 100 users can take 100GB of storage space, which can add up!

- Bandwidth blocking: An attacker can crash your email service or bring it to a crawl by filling the incoming Internet connection with junk. Even if your system automatically identifies and discards obvious attachment attacks, the bogus messages eat resources and delay processing of valid messages.

- Storage overload: Multiple large messages can quickly fill the total storage capacity of an email server. If the messages aren’t automatically deleted by the server or manually deleted by individual user accounts, the server will be unable to receive new messages.

- An email hack on a single email address can have serious consequences if the address is for an important user or group.

Countermeasures against email attachment attacks

These countermeasures can help prevent attachment-overload attacks:- Limit the size of emails or email attachments. Check for this option in your email server’s configuration settings (such as those provided in Microsoft Exchange), in your email content filtering system, and even at the email client level.

- Limit each user’s space on the server or in the cloud. This countermeasure denies large attachments from being written to disk. Limit message sizes for inbound and even outbound messages if you want to prevent a user from launching this attack from inside your network. Typically, a few gigabytes is a good limit, but the limit depends on your network size, storage availability, business culture, and so on. Think through this limit carefully before putting one in place.

Consider using SFTP, FTPS, or HTTPS instead of email for large file transfers. Numerous cloud-based file transfer services are available, such as Dropbox for Business, OneDrive for Business, and Sharefile. You can also encourage your users to use departmental shares or public folders. By doing so, you can store one copy of the file on a server and have the recipient download the file on his or her own workstation.

Contrary to popular belief and use, the email system should not be an information repository, but that’s exactly what email has evolved into. An email server used for this purpose can create unnecessary legal and regulatory risks and can turn into a huge nightmare if your business receives an e-discovery request related to a lawsuit. An important part of your security program is developing an information classification and retention program to help with records management. But don’t go it alone. Get others such as your lawyer, human resources manager, and chief information officer involved. This practice can help ensure that the right people are on board and that your business doesn’t get into trouble for holding too many — or too few — electronic records in the event of a lawsuit or investigation.

Email hacking: Connections

A hacker can send a huge number of emails simultaneously to hack your email system. Malware that’s present on your network can do the same thing from inside your network if your network has an open Simple Mail Transfer Protocol (SMTP) relay (which is often the case). These connection attacks can cause the server to give up on servicing any inbound or outbound Transmission Control Protocol (TCP) requests. This situation can lead to a server lockup or a crash, often resulting in a condition in which the attacker is allowed administrator or root access to the system.Attacks using floods of emails

An email hack using a flood of emails is often carried out in spam attacks and other DoS attacks.Countermeasures against email attachment attacks

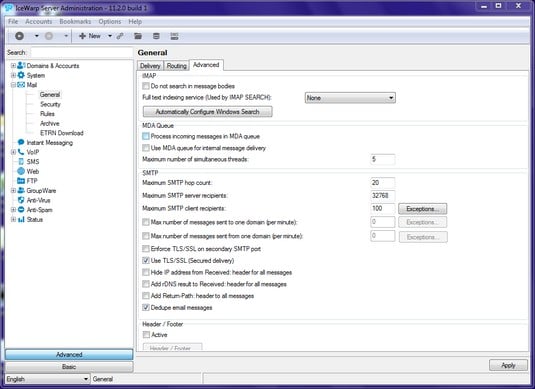

Prevent email hacks as far out on your network perimeter as you can, ideally in the cloud. The more traffic or malicious behavior you keep off your email servers and clients, the better.Many email servers allow you to limit the number of resources used for inbound connections, as shown in the Maximum Number of Simultaneous Threads setting for the IceWarp email server. This setting is called different things for different email servers and firewalls, so check your documentation. Completely stopping an unlimited number of inbound requests can be impossible, but you can minimize the impact of the attack. This setting limits the amount of server processor time, which can help during a DoS attack.

Limiting the number of resources that handle inbound messages.

Limiting the number of resources that handle inbound messages.Even in large companies, or if you’re using a cloud-based email service such as G Suite or Office 365, there’s likely no reason why thousands of inbound email deliveries should be necessary within a short period.

Email servers can be programmed to deliver emails to a service for automated functions, such as create this e-commerce order when a message from this account is received. If DoS protection isn’t built into the system, an attacker can crash both the server and the application that receives these messages, potentially creating e-commerce liabilities and losses. This type of attack can happen more easily on e-commerce websites when CAPTCHA (short for Completely Automated Public Turing test to tell Computers and Humans Apart) isn’t used on forms. This can be problematic when you’re performing web vulnerability scans against web forms that are tied to email addresses on the back end. It’s not unusual for this situation to generate thousands, if not millions, of emails. It pays to be prepared and to let those involved know that the risk exists.

Automated email security controls to guard against email hacking

You can implement the following countermeasures as an additional layer of security to guard against email hacks:- Tarpitting: Tarpitting detects inbound messages destined for unknown users. If your email server supports tarpitting, it can help prevent spam or DoS attacks against your server. If a predefined threshold is exceeded — say, more than 100 messages in one minute — the tarpitting function effectively shuns traffic from the sending IP address for a given period.

- Email firewalls: Email firewalls and content-filtering applications from vendors such as Symantec and Barracuda Networks can go a long way toward preventing various email attacks. These tools protect practically every aspect of an email system.

- Perimeter protection: Although not email-specific, many firewall and intrusion prevention systems can detect various email attacks and shut off the attacker in real time, which can come in handy during an attack.

- CAPTCHA: Using CAPTCHA on web-based email forms can help minimize the impact of automated attacks and lessen your chances of email flooding and DoS, even when you’re performing seemingly benign web vulnerability scans. These benefits really come in handy when you test your websites and applications.