Few things are more disruptive to operations management than poor quality. Poor quality has a negative impact on all your process metrics. You will need to know how to manage your process given the current quality levels.

Poor quality wastes resources in three ways:

By producing the bad part in the first place

By having to “fix” the bad part (often called rework)

By having to find bad parts before they progress in the process or, in the worst case, before they’re sold to a customer

When you find defects in a product, you can either fix what’s wrong or scrap the product. If you discard the product, you waste the time and materials that went into the product. If you attempt to fix the defect, you must use resources on the rework that could be used making additional products.

You can handle rework in two ways: You can establish a separate process to handle the defective products or place them back in the main process that created them and correct the defect.

Put rework back in the process that created it

Sometimes, when a defective product is discovered, it’s repaired/fixed by the resource that created it and then placed back into the process where the defect occurred.

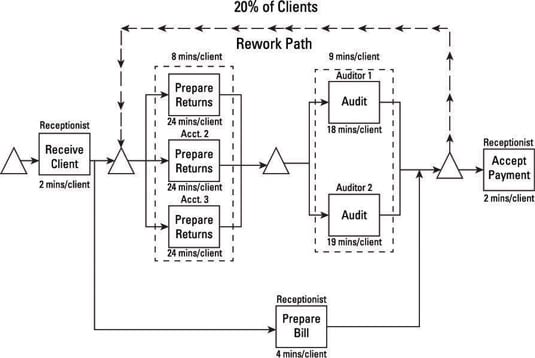

In this process, a customer enters the system, and a receptionist greets him. He then waits for one of the three accountants. After an accountant completes his tax return, one of the two auditors checks it for accuracy. If the return is correct, the customer pays the receptionist, who prepared his bill while the return was being processed and audited.

If returns aren’t defective, then the accountants and the receptionist have a cycle time of 8 minutes and a capacity of 7.5 clients per hour. The system bottleneck (slowest resource) is the auditors, who have a cycle time of 9 minutes, giving them a capacity to process 6.67 customers per hour.

If the auditors discover that 20% of the returns have a mistake, then the return goes back to an accountant (not necessarily the one who initially worked on the return). The accountant spends an additional 24 minutes correcting the return, and the auditor must spend an additional 4 minutes rechecking it for accuracy. Assume that the return is correct the first time through the rework cycle.

To analyze this process when rework is involved, the first thing you must do is calculate the new cycle times for the accountants and the auditors. To do this, you want to calculate the cycle time for a part that requires rework and the cycle time of a good part. You can then take a weighted average to obtain a new average cycle time.

In the example, the accountant spends a total of 24 minutes on a good return and 48 minutes on a return requiring rework (24 minutes the first time plus an additional 24 minutes to fix the return). With 20% of the returns requiring rework, the new average cycle time is 28.8. With three accountants, the cycle time of the activity is 9.6 minutes.

Similarly, an auditor spends 18 minutes on a good return and 22 minutes (18 minutes plus 4 minutes for rework) on a return requiring rework, giving a new average cycle time of 18.8 minutes. With two auditors, the cycle time of the activity is 9.4 minutes.

A danger of the rework cycle is that the bottleneck of the process may change. If your bottleneck changes without your realizing it, you’ll try to optimize the wrong resource and won’t see any process improvement as a result of your efforts.

In this example, the accountants are now the bottleneck, and the process now has a capacity of 6.25 clients per hour. Because of the rework, the process capacity is reduced by 0.42 clients per hour, or 3.36 per 8-hour day.

Assuming a 5-day work week, this means that, over the 6 weeks before April 15, which is the peak time for income tax filing, the firm would lose capacity of more than 100 clients. That adds up to a lot of money lost over a short period of time.

How to pull rework out of the main process

Placing a defective part back into the main process is often hard, if not impossible. For example, consider an automobile assembly line. Moving a defective auto and placing it back on the line for repair would be extremely disruptive and costly.

Usually, a company uses resources other than the main line resources to correct quality problems. This creates a lot of waste for the organization. You need not only additional resources but also additional space and equipment to process the defective part.

In the example involving tax returns, placing defective returns back into the process is easy, but you could also handle them off the main process flow. You could hire additional personnel dedicated to handle rework or assign one of the main line accountants and auditors to perform rework as well. The latter option would mean using resources across multiple processes, which may create a problem of its own.