The exit strategy is the most important part of the job for a venture capital (VC) company. In most cases, the only way a VC makes money is when the company is sold through an initial public offering (IPO) or is acquired by another company (merger and acquisition, or M&A) or a private equity firm.

This is a key reason why, if your plan for your company is to run it for the rest of your life as a private corporation, a VC will probably not be interested. In this situation, she has no way to return the cash to investors. But being sold or acquired isn’t the sole objective: The key is to be sold for a very high return on investment (ROI).

Venture capital: Look at ROI

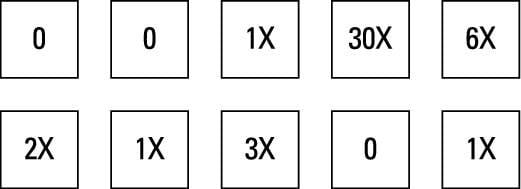

The venture capital model is based on hitting the business equivalent of homeruns. In a portfolio of ten investments, typical VCs can expect more than half to do very poorly. This figure shows an example portfolio in which, of ten investments, three are a total loss, three return the initial investment back, three earn between 2X and 6X the initial investment, and one is a “home run” at 30X the initial investment.

This requirement is one of the reasons why deals that are limited to returning only 5X the investment are never in a VCs portfolio. Small ROI deals have all the risk and none of the possibilities.

Many entrepreneurs offer a buy-back of stock as the potential exit strategy. In most cases, this plan is unrealistic. If an investor looks for a 10X return on investment, there is almost no way that a company can return that investment in cash.

Here’s why: Company value is rarely found simply in cash flow but is typically measured in multiples of EBITDA (earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization) that are often many times the company’s current cash flow. In this scenario, the company won’t have sufficient cash on hand to pay the VC for her equity.

Venture capital: Plan the exit

Most of the value of the deal comes at the exit, and planning and executing the exit strategy is a key role of the VC. To have a successful exit, several key conditions must exist: rapid growth, a strong and coherent management team, a favorable market and economic conditions for acquisition or IPO, and sufficient traction to justify acquisition by a key player in the market.

Understanding that the exit is not just something to be put together at the end, the VC begins planning the exit well in advance, engineering it into the company from the very beginning.

Perhaps even more valuable than knowing how to plan an exit, VCs also know who the strategic acquirers are in your industry, and they probably already have relationships with them. VCs also have the knowledge and expertise to know whether IPO or acquisition is a better strategy for your firm.

Not all companies will have an exit at all, or the exit may be that the company is shut down and liquidated. This can happen when growth doesn’t hit projections or when the industry or market changes significantly with new competitive pressures or technologies that eliminate your company’s strategic advantage.

Other companies, considered the “walking dead,” are ones that return a small amount of cash flow to investors, but their chances of being acquired are negligible. Success in a venture capital–backed firm happens less than half the time, so entrepreneurs need to be fully committed while also understanding that failure is an option.

How venture capitalists make money off the deal

VCs make money in three ways:

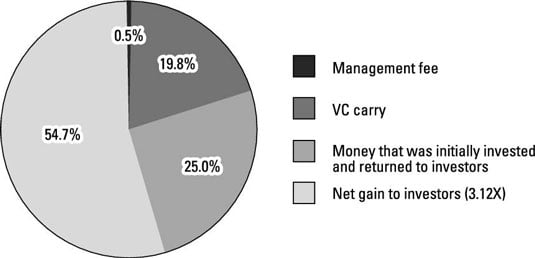

Management fee: The VC firm earns a management fee that covers its costs for creating deal flow, screening, due diligence, serving on boards, coaching, accounting and reporting, and engineering the exit.

The firms typically make 2 percent of the money under management for these services. A $100 million fund, for example, makes $2 million in management fees, which are used to pay all the staff members and keep the lights on in the office.

Carried interest at the exit: VCs make money at the exit through carried interest, which is generally called a carry in investor lingo. The carried interest is typically equal to 20 percent of the net profit after an exit.

If, for example, the fund invested $100 million in ten companies and returned $200 million after all the exits, the VC would be entitled to a carry of $20 million. The carried interest ensures that the VC is focused on developing the greatest possible return for the fund.

Interest from investing their own money: Sometimes VCs get an option to invest their own money into the fund — a big perk for senior staff members (junior staff are often not allowed to invest alongside the firm).

Having her own money invested in the fund shows a personal commitment to the fund and ensures alignment between the fund managers and the limited partners because they all share the risk of investment.

When a venture fund loses money, the VC loses not only her own investment, but the opportunity to participate in the carried interest as well. VCs are very motivated not to lose money!

This figure shows the VCs’ return on investment after a liquidation event and where the money goes.