A high-note riff on the guitar is very close — in words and in music — to a lick. So, just forget the whole idea of strictly defining terms in such a forgiving and nonjudgmental form as the blues. But if you’re mastering all that low-note stuff, you deserve to see what awaits you when you ascend the cellar stairs into the sunshine of high-note, melodic-based playing.

Quick-four riffs

A quick-four refers to a double-stop riff that you play on the 2nd and 3rd strings within a measure of a I or IV chord. (Don’t get this quick-four confused with the kind of quick four that happens in bar two of a 12-bar blues.) When you play this riff during a chord, you create a temporary IV chord.

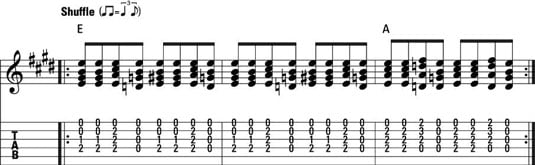

The Rolling Stones’ Keith Richards carved out a very successful career exploiting this riff, and he learned from the great American blues masters. Here is a four-bar phrase where the quick-four riff is applied at the end of each bar of an E and A chord.

Keith Richards’s signature riffs in Stones classics like “Brown Sugar,” “Honky-Tonk Women,” and “Start Me Up” are actually in open-G tuning, which makes the quick-four easier to access. Open tunings in G, A, D, and E were used extensively by prewar acoustic guitarists — such as Charlie Patton, Son House, and Robert Johnson — especially for slide playing.

Intro, turnaround, and ending riffs

Intros, turnarounds, and ending riffs fill out the chord structure with melodic figures. As you play these figures, try to hear the underlying structure — the rhythm guitar in your mind — playing along with you. You can play the chords according to the chord symbols above the music, but in this case the symbols identify the overall harmony and don’t tell you what to actually play at that moment.

Intro, turnaround, and ending riffs have very similar DNA, so they can be mutated ever so slightly to change into the others. The figures you’ll see here provide examples that you can easily adapt and add your own flavor to. These practices get you used to taking other people’s ideas and fashioning them into your own. That’s how pre-existing riffs and licks get turned into an individual and original voice.

Intro riffs

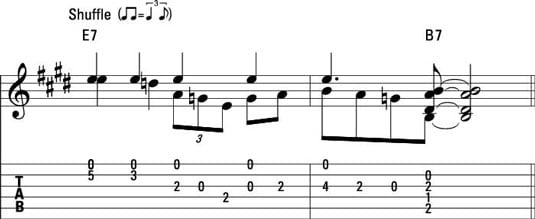

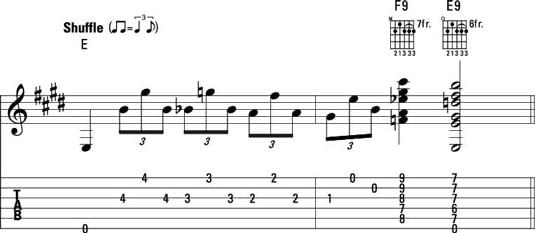

This is a snappy, triplet-based intro riff. The lower voice descends while the top voice stays fixed. Try playing this riff fingerstyle or with a pick and fingers.

This is related to the above example in that the lower voice descends against a fixed upper-note. But here, the notes are played together as double-stops for a more obvious and dramatic harmonic clash of the two notes. This blues lick is borrowed from a famous pop song — Johnny Rivers’s version of Chuck Berry’s “Memphis.” Play this lick fingerstyle or with pick and fingers.

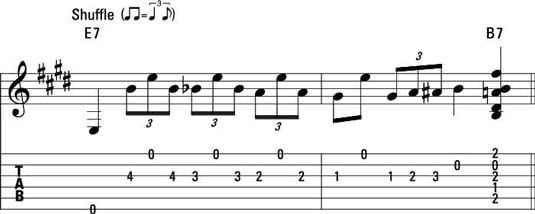

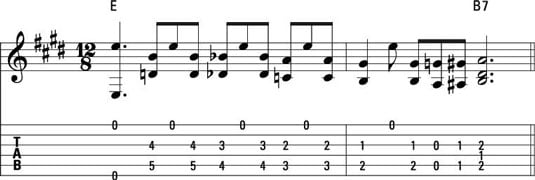

The varying motion of this riff makes it unpredictable and dramatic. The figure shows an all-single-note riff in triplets, ending in a B7 chord that comes on beat two. The melody here changes direction often and can be a little tricky at first.

But you can get the hang of it with some practice. The last note of the melody, low B, is actually the root of the B7 chord that you play one moment later. So play that B with your left-hand 2nd finger.

Turnaround riffs

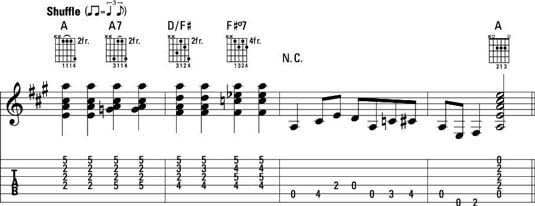

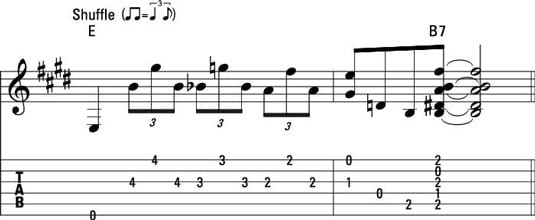

This riff can be used as an intro or a turnaround, but here it’s cast as a turnaround. This is a double-stop riff in A with a descending lower voice, reminiscent of the playing of Robert Johnson.

Here is a wide-voiced double-stop riff where the voices move in contrary motion (the bass ascends while the treble descends). This riff is great for any fingerstyle blues in E because it highlights the separation of the bass and treble voices — a signature feature of the fingerstyle approach.

If the double strikes in the bass give you trouble at first, try playing them as quarter notes, in lock step with the treble voice.

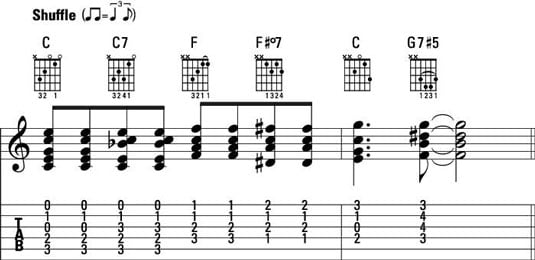

This is an open-chord turnaround riff in C — the key for fingerpicking country blues like Mississippi John Hurt. The last chord is a treat: a jazzy G7 augmented (where the fifth of the chord, D, is raised a half step to D♯), which gives the progression a gospel feel with a little extra flavor.

Ending riffs

Ending riffs are similar to both intros and turnarounds, except ending riffs terminate with the I chord, not the V.

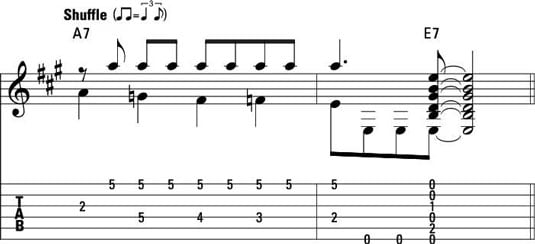

What you see here is a triplet-based riff in sixths, where the second string isn’t played. You can play this riff with just the pick, but it’s easier with fingers or a pick and fingers. The open B string on the last triplet of beat one gives you a bit of a head start to get your hand up the neck to play the F9 and E9 ending chords.

This is a low note ending in E, using triplet eighths and a double-stop descending form. This riff is meaty and doesn’t sound too melodic because it has more of a low, walking bass feel.

Here is something completely different: a ragtime or country-blues progression in A. The more complex-sounding chords and the voice leading (where each note resolves by a half or whole step to the closest chord tone) give the riff a tight, barbershop sound. You hear this type of progression in the playing of the great country-blues fingerstyle-players like Mance Lipscomb, Fred McDowell, Mississippi John Hurt, Reverend Gary Davis, and Taj Mahal.