This list of human abilities represents some of the ideas of what intelligence actually is; these abilities are the stuff of intelligence. For a more concrete definition, intelligence can be understood as a collection of cognitive abilities that allows a person to learn from experience, adapt successfully to the world, and go beyond information presented in the environment.

Acting intelligently is probably the most grand cognitive process of the human mind. After all, managing information and the various components of attention and remembering things ought to produce something useful, right? You can view intelligence as the collective output of human cognition that results in an ability to achieve goals, adapt, and function in the world. This is intelligent behavior.

The factors of intelligence

Sure, intelligence is a collection of cognitive abilities, but a unifying construct called “intelligence” that can be measured and quantified must exist, right? Psychologists think so, and they’ve been working tirelessly to test and measure intelligence for a long time. As part of this work, psychologists have developed intelligence tests and worked with militaries, schools, and corporations, trying to sort individual differences in intelligence in the service of job selection, academic honors, and promotions. From all this testing has emerged the concept of “g” as a general and measurable intelligence factor.The g-factor is comprised of subcomponents known as s-factors. Together, the g- and s-factors comprise what is called the two-factor theory of intelligence:

- g-factor: Some psychologist comes up with a test of mental abilities and gives it to a lot of people. When a score is calculated and averaged across abilities, a general intelligence factor is established. This is factor one of the two-factor theory, commonly referred to as the g-factor, or the general intelligence factor. It is meant to represent how generally intelligent you are, based on your performance on this type of intelligence test.

- s-factor: The individual scores on each of the specific ability tests represent the s-factors. An s-factor score represents a person’s ability within one particular area. Put all the s-factors together, and you get the g-factor. Commonly measured s-factors of intelligence include memory, attention and concentration, verbal comprehension, vocabulary, spatial skills, and abstract reasoning.

Psychologist and intelligence research pioneer Louis Thurston (1887–1955) came up with a related theory of intelligence called primary mental abilities. It’s basically the same concept as the s-factor part of the two-factor theory, with a little more detail. For Thurston, intelligence is represented by an individual’s different levels of performance in seven areas: verbal comprehension, word fluency, number, memory, space, perceptual speed, and reasoning. Thurston’s work, however, has received very little research support.

Cattell-Horn-Carroll Theory of Cognitive Abilities

Psychologists continue to divide general intelligence into specific factors. The Cattell-Horn-Carroll Theory of Cognitive Abilities (CHC Theory) proposes that “g” is comprised of multiple cognitive abilities that when taken as a whole produce “g.” The individual contributors to CHC theory (Raymond Cattell, John Horn, and John Carroll) produced a model of general intelligence consisting of ten strata. They are as follows:- Crystallized intelligence (Gc): comprehensive and acquired knowledge

- Fluid intelligence: reason and problem-solving abilities

- Quantitative reasoning: quantitative and numerical ability

- Reading and writing ability: reading and writing

- Short-term memory: immediate memory

- Long-term storage and retrieval: long-term memory

- Visual processing: analysis and use of visual information

- Auditory processing: analysis and use of auditory information

- Processing speed: thinking fast and automatically

- Decision and reaction speed: coming to a decision and reacting swiftly

Many intelligence researchers and practitioners have accepted CHC as a triumph of psychological science and the consensus model of psychometric conceptions of intelligence. It is, however, a working model, and many intelligence investigators and theorists consider CHC theory as a strong beginning but not the final word on intelligence.

Street smarts

American psychologist Robert Sternberg developed the Theory of Successful Intelligence in part to address the street smarts controversy, which holds that many intelligent people may be smart when it comes to academics or the classroom but lack common sense in real life or practical matters.A cultural myth claims that Albert Einstein, unquestionably gifted in mathematics and physics, couldn’t tie his own shoes. I don’t know if this is true or not, but Sternberg seems to agree that an important aspect of being intelligent is possessing a good level of common sense or practical intelligence. The three intelligence components of his theory are as follows:

- Analytical intelligence: The ability to analyze, evaluate, judge, decide, choose, compare, and contrast.

- Creative intelligence: The ability to generate unique or creative ways to deal with novel problems.

- Practical intelligence: The type of intelligence used to solve problems and think about actions of everyday life. Like Einstein tying his shoes, opening up a jar of pickles, how to send a group text, or figuring out how to change your face into an alien with the latest photo filtering app.

Multiple intelligences

Have you ever wondered what made Michael Jordan such a good basketball player? What about Mozart's musical ability? He wrote entire operas in one sitting without editing. That’s pretty impressive! According to American psychologist Howard Gardener, each of these men display a specific type of intelligence.Gardener generated a theory known as multiple intelligences from observing extremely talented and gifted people. He came up with seven types of intelligence that are typically left out of conventional theories about intelligence:

- Bodily kinesthetic ability: Michael Jordan seems to possess a lot of this ability. People high in bodily kinesthetic ability have superior hand-eye coordination, a great sense of balance, and a keen understanding of and control over their bodies while engaged in physical activities.

- Musical ability: If you can tap your foot and clap your hands in unison, then you’ve got a little musical intelligence — a little. People high in musical intelligence possess the natural ability to read, write, and play music exceptionally well.

- Spatial ability: Have you ever gotten lost in your own backyard? If so, you probably don’t have a very high level of spatial intelligence. This intelligence involves the ability to easily move around in space and to picture three-dimensional scenes in your mind.

- Linguistic ability: This is the traditional ability to read, write, and speak well. Poets, writers, and articulate speakers are high in this ability.

- Logical-mathematical ability: This intelligence includes basic and complex mathematical problem-solving ability.

- Interpersonal ability: The gift of gab and the used-car salesman act are good examples of interpersonal intelligence. A “people person” who has good conversational skills and knows how to interact and relate well with others is high in interpersonal ability.

- Intrapersonal ability: How well do you know yourself? Intrapersonal intelligence involves the ability to understand your motives, emotions, and other aspects of your personality.

Making the intelligence grade — on a curve

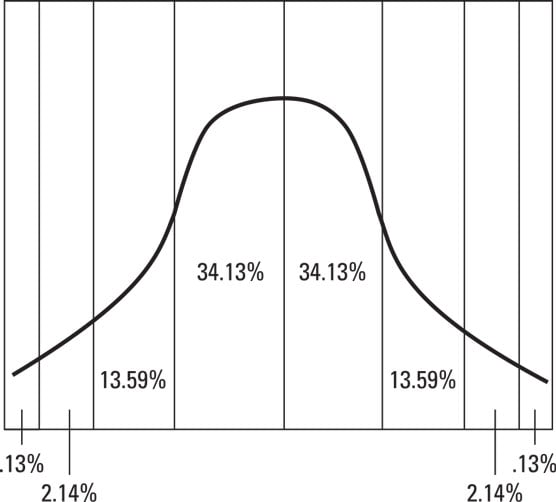

Psychologists like to measure stuff, especially stuff related to human behavior and thought processes, like cognitive abilities. Measuring and documenting individual differences is at the core of applied psychological science.Whether you ascribe to CHC, Sternberg’s model, or the concept of multiple intelligences, don’t forget the concept of average. Intelligence is considered to exist in the human population along what is called a normal distribution. A normal distribution is essentially a statistical concept that relates to the ultimate range of any particular trait or psychological phenomenon across a population.

Individuals vary in how intelligent they are. A normal distribution (see the following figure) is established by assuming that if the full population took an intelligence test, most people would center around average scores with some variation — from slightly less than average to slightly higher than average.

A normal distribution is also referred to as a bell curve because it looks like a bell with a bulky center and flattening right and left ends. Most people are somewhere in the range of average intelligence. Increasingly fewer people are at intelligence levels that are closer to the highest and lowest ends of the spectrum.

Normal distribution

At the high end of the intelligence curve are people considered intellectually gifted; at the low end are those considered intellectually disabled.

Shining bright

Einstein was a genius, right? So what exactly is a genius?Psychologists typically refer to super-smart people as intellectually gifted rather than using the term genius. But there is no uniform cutoff score on an intelligence test to determine giftedness. An average standard intelligence score is 100 and, generally speaking, any score above 120 is considered superior. Giftedness is granted to people in the top 1 to 3 percent of the population. That is, out of 100 people, only one, two, or three are considered gifted.

Many psychologists are wary of defining giftedness in such numerical and statistical terms and warn that cultural and societal context must be factored in. Could one culture’s genius be another culture’s madman? I’m not sure it’s that dramatic, but it is important to consider that giftedness is multifaceted and not so easily tied to a cutoff score.

Numerous attempts have been made to pin down a definition of intellectual giftedness. Robert Sternberg proposed that giftedness is more than superior skills related to information processing and analysis; it also includes superior ability to capitalize on and learn from one’s experiences to quickly solve future problems and automatize problem solving. He proposed that gifted people are especially skilled at adapting to and selecting optimal environments in a way that goes beyond basic information processing and what is considered general intelligence or “g.”Researchers continue to examine the concept of intellectual giftedness, and one consistent finding is that gifted individuals have stronger metacognitive skills, or knowledge of their own mental processes and how to regulate them. These three specific metacognitive strategies are often used by gifted individuals:

- Selective encoding: Distinguishing between relevant and irrelevant information

- Selective combination: Pulling together seemingly disparate elements of a problem for a novel solution

- Selective comparison: Discovering new and nonobvious connections between new and old information