In managerial economics, game theory helps to figure out the best business decision to make. For example, you’ve developed a highly-regarded bike shop in the local community. A larger neighboring community has a bike shop owned by a rival. Your rival’s bike shop is larger and you fear that the rival may be considering entering your market.

You need a strategy that enables you to preempt your rival. This is an obvious game theory situation where you must take into account your rival’s actions.

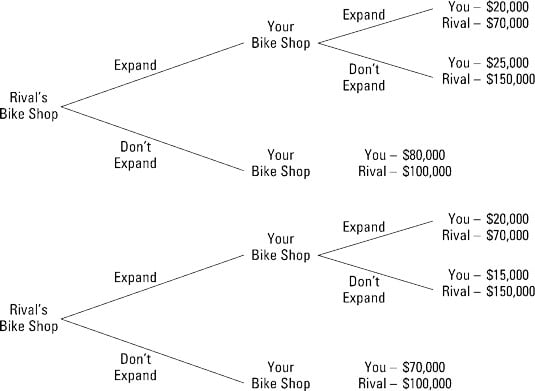

Assume the possible scenarios are represented by the decision trees in the illustration with the payoff being annual profit. The upper panel describes the current situation. If your rival expands, you can either expand or not expand. Using backward induction, your rival takes the following steps:

If your rival doesn’t expand, the status quo continues.

The status quo is represented by the lower branch on the decision tree. If your rival doesn’t expand, you won’t do anything — there are no branches for your decision — and the profits are $100,000 for your rival and $80,000 for you.

If your rival expands, you don’t expand.

If your rival expands, you don’t expand because if you expand your profits are $20,000 versus if you don’t expand, your profits are $25,000.

Your rival decides to expand by using backward induction.

Given you don’t expand, your rival earns $150,000 by expanding into your community, while the rival earns only $100,000 if it doesn’t expand. And the bad news for you is your profit is only $25,000. You aren’t likely to enjoy this game, so how can you change it?

You engage in a preemptive strategy by renting a store location in your rival’s community for $10,000 a year.

This is how much you would have to pay if you decide to expand into your rival’s community. This changes the decision tree by lowering your profit by $10,000 in every situation you don’t expand because of the added expense you incur. It doesn’t change your expense if you do expand — you need the store.

So in the decision tree in the lower panel, your profit for when both you and your rival expand doesn’t change — it remains $20,000. Your profit for when your rival expands but you don’t expand goes down by $10,000 from $25,000 to $15,000 because of the rent you pay on the unoccupied store front.

Similarly, your profit if your rival decides not to expand goes down by $10,000 for the unoccupied store front, from $80,000 to $70,000.

Your rival uses backward induction.

If your rival doesn’t expand, the status quo continues. The profits are $100,000 for your rival and now only $70,000 for you.

If your rival expands, you also expand.

If you don’t expand, your profit is $15,000. If you expand, your profit is $20,000.

If both you and your rival expand, your rival earns $70,000 profit.

This combines both decisions to expand.

Your rival decides not to expand.

By not expanding, your rival earns $100,000 profit as opposed to only $70,000 profit if your rival expands.

Your preemptive strategy changes your rival’s behavior. Not taking the preemptive strategy results in you earning $25,000 profit. By spending $10,000 to rent a store front you never plan to use, you increase your profit to $70,000.