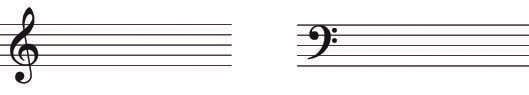

To play the piano or keyboard, you need to know that notes and rests in music are written on what’s called a musical staff. A staff is made of five parallel horizontal lines, containing four spaces between them.

Notes and rests are written on the lines and spaces of the staff. The particular musical notes that are meant by each line and space depend on which clef is written at the beginning of the staff. You may run across any of the following clefs:

Treble clef

Bass clef

C clefs, including alto and tenor

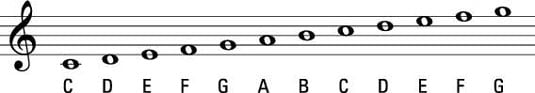

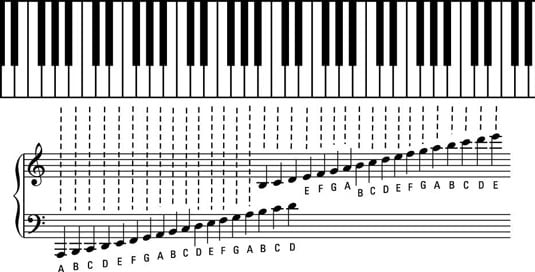

Think of each clef as a graph of pitches, or tones, shown as notes plotted over time on five lines and four spaces. Each pitch or tone is named after one of the first seven letters of the alphabet: A, B, C, D, E, F, G, A, B, C … and it keeps on going that way indefinitely, repeating the note names as the pitches repeat in octaves.

The pitch ascends as you go from A to G, with every eighth note — where you return to your starting letter — signifying the beginning of a new octave.

The treble clef

The treble clef is for higher-pitched notes. It contains the notes above middle C on the piano, which means all the notes you play with your right hand. The treble clef is also sometimes called the G clef. Note that the shape of the treble clef itself resembles a stylized G. The loop on the treble clef also circles the second line on the staff — which is the note G.

The notes are located in the treble clef on lines and spaces, in order of ascending pitch.

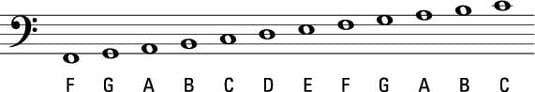

The bass clef

On the piano, the bass clef contains lower-pitched notes, the ones below middle C, including all the notes you play with your left hand. Another name for the bass clef is the F clef. The curly top of the clef partly encircles where the F note is on the staff, and it has two dots that surround the F note line.

The notes on the bass clef are also arranged in ascending order.

The grand staff and ledger lines

Sooner or later, on either staff, you run out of lines and spaces for your notes. Surely the composer wants you to use more of the fabulous 88 keys at your disposal, right? Here’s a solution: Because you play piano with both hands at the same time, why not show both staves (the plural form of staff ) on the music page? Great idea!

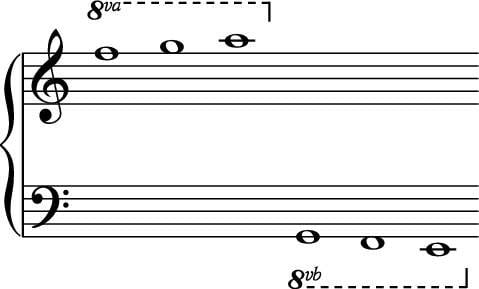

Join both staves together with a brace at the start of the left side and you get one grand staff. This way, you can read notes for both hands at the same time.

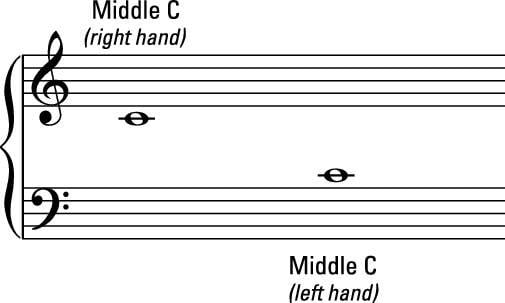

Why all the space between the two staves? Note that the bottom line of the treble clef staff is E, and the top line of the bass clef staff is A. That space is for the notes between those two notes.

That’s where ledger lines come in. Ledger lines allow you to notate the notes above and below each staff. Middle C, for example, can be written below the treble staff or above the bass staff by using a small line through the notehead. Either way, it’s the same note on the piano keyboard.

If middle C is written with a ledger line below the treble staff, you play it with your right hand; if it’s written with a ledger line above the bass staff, you play it with your left hand.

If you’re more of a visual learner, try thinking of it this way: The notes written in the middle of the grand staff, or between the two staves, represent notes in the middle of the piano keyboard.

The ledger line represents an imaginary line running above or below the staff, extending the five-line staff to six, seven, or more lines. You can, of course, read notes in the spaces between the ledger lines just like you read notes in the spaces between the staff lines.

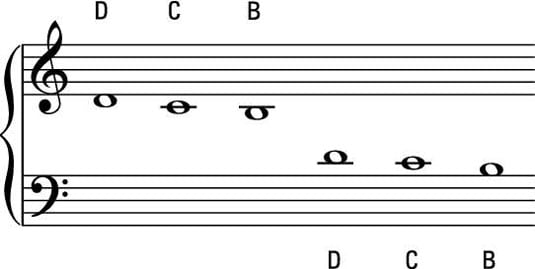

The notes B and D, surrounding middle C, can also be written by using ledger lines. That is, D can either be written below the bottom line of the treble staff, or it can sit on top of the middle C ledger line above the bass staff. Similarly, B can sit on top of the bass staff or below the middle C ledger line of the treble staff.

Beyond the staff

Middle C may be powerful, but it isn’t the only note to receive the coveted ledger line award. Other ledger lines come into play when you get to notes that are above and below the grand staff. Notes written above the treble staff represent higher notes, to the right on your keyboard. Conversely, notes written below the bass staff represent lower notes, to the left on your keyboard.

For example, the top line of the treble staff is F. Just above this line, sits the note G. After G, a whole new set of ledger lines waits to bust out.

A similar situation occurs at the bottom of the bass staff. Ledger lines begin popping up below the low G line and low F that’s hanging on to the staff for dear life.

An octave above, an octave below

Writing and reading ledger lines for notes farther up and down the keyboard can get a little ridiculous. After all, if you were to keep using ledger lines, you’d take up an impractical amount of space, and reading all those lines would become tedious.

That’s why composers invented the octave, or ottava line, which tells you to play the indicated note or notes an octave higher or lower than written. The abbreviation 8va means play an octave above, and 8vb means play an octave below.