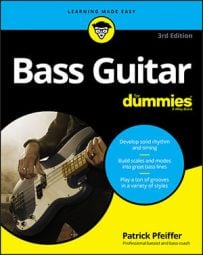

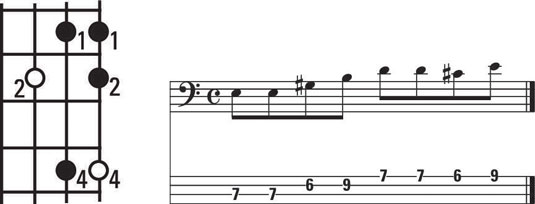

Rock ’n’ roll refers to the style of rock that originated in the 1950s and ’60s (think Elvis Presley or Buddy Holly). The bassist maintains a quarter-note or eighth-note rhythm and a distinctive melodic bass line that spells out the harmony for the band and the listener. The example uses one note — the root — with an eighth-note rhythm. (The open circle on the grid represents the root.)

As you listen to this rock ‘n’ roll groove in Chapter 8, Audio Track 57, notice how the rhythm of the notes (at the start of the track) is evenly divided and how the bass locks in with the drums. You can also watch this rock ‘n’ roll groove in Chapter 8, Video Clip 20.

You can start the groove with any finger, because only one note is used — the root. You also don’t have to worry about the chord tonality.

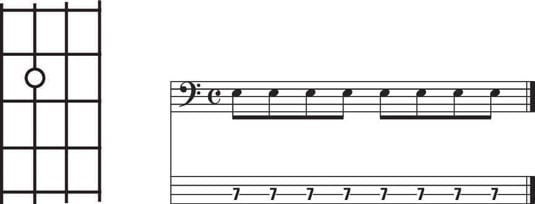

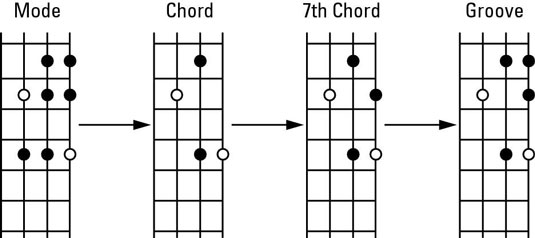

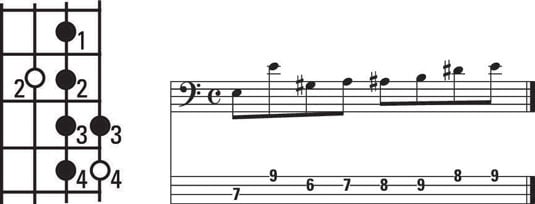

Then, you add the 3 and 5 (the third and fifth notes of the major scale) to the groove to form the chords. In the grid, the root is the open circle, and the solid black dots are the other chord tones (the notes in the chord). It has to be played with your middle finger on the root to avoid shifting during the groove.

Notice how the eighth notes are driving the rhythm. The bass and drums are tightly locked in with each other. The choice of the bass notes indicates to the band members the tonality of the chords: major, minor, or dominant.

You can alter the examples to fit any tonality. Simply lower the regular 3 to a ♭ó3 to change the tonality from major to minor, or raise the ♭ó3 to a regular 3 to change it from minor to major. This change isn’t a major problem, just a minor adjustment.

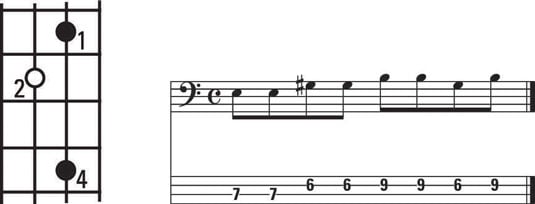

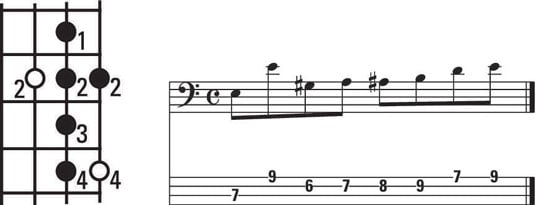

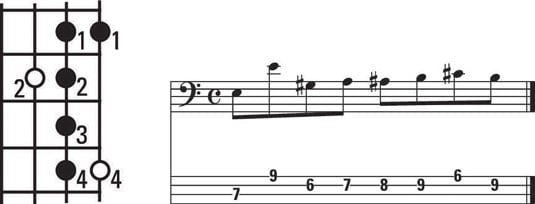

This groove shown is the same as the one above with one exception: This groove has a minor 3 (♭ó3) instead of a major 3 (or 3). The lowering of the major 3 to the ♭ó3 changes the entire chord into a minor chord. Start this groove with your index finger on the root to avoid any unnecessary shifting of your left hand.

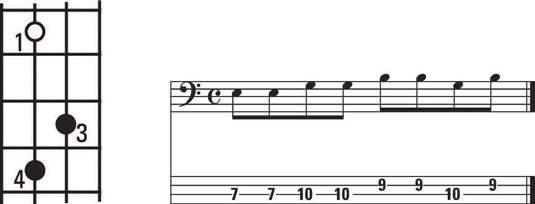

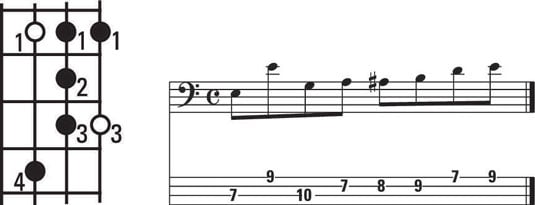

Here is an example of a more elaborate rock ’n’ roll groove, using notes that come not only from the major chord but also from the Mixolydian mode (scale), making it dominant. Start this groove with your middle finger on the root.

This groove fits nicely over a dominant chord, which is a common chord in rock ’n’ roll. The dominant chord consists of the root, 3, 5, and ♭ó7 of the Mixolydian mode. Here’s the thought process.

For a denser rock ’n’ roll groove, check out this groove, which includes not only notes from the chord and its related mode (Mixolydian in this case) but also chromatic tones — notes outside the regular mode that lead to the notes within the chord.

You can play all the notes of this groove in the same position, as long as you start with your middle finger. This is called a box groove because the positioning of the notes forms a box; your left hand is positioned so that your fingers can reach all the notes without shifting.

You can alter the previous groove to play over a minor tonality by lowering the 3 to ♭ó3, which converts the dominant chord tonality into a minor tonality. To play this groove, start with your index finger on the root so you don’t have to shift your left hand.

You also can convert this groove into a major 7th tonality. To do so, raise the ♭ó7 of the original groove and then play the groove using a major 7th chord (root, 3, 5, and 7). Begin with your middle finger on the root. The major 7th tonality is rare in rock ’n’ roll, but it’s still useful to know how to play it.

When accompanying a rock tune that has a major 7th tonality, you may want to substitute the 6 of the major mode for the 7 in your groove. The 6 softens the sound and makes it more pleasant to the ear. The 7 is very rarely used in a groove. Take a look at this example to see the use of a 6 in a major 7th tonality.

With the 6 in place, you can use the groove over a major 7th tonality as well as over a dominant tonality. The only difference between these two tonalities is the 7: The major 7th chord has a regular 7, and the dominant chord has a ♭ó7. A groove with a regular 7 clashes with a dominant chord; a groove with a ♭ó7 clashes with a major chord.

In the above groove, however, the 6 doesn’t clash with either chord. (In fact, it sounds pretty good.) You can use this groove to give the other players of your band more leeway in their choice of notes. It doesn’t lock them into having to choose between either a 7 or ♭ó7.

One groove can be adapted to fit over different tonalities: the dominant, the minor, the major 7th, and a major tonality with a 6 rather than a 7.

You can change the sound of a groove to a different tonality by changing the 3, the 7, or even the 5. Check out the sounds of Adam Clayton of U2 or of the late John Entwistle of The Who if you want to hear some great rock bassists.