You can take some measures in your operations management to help prevent the decline of a product or to avoid it stalling out in the saturation phase. Some products, such as baking soda or refrigerators, are fortunate enough to never reach the decline phase; they remain in the saturation phase for eternity, usually at a lower sales level than they reached at their peak.

Repositioning

One tried-and-true method of breathing new life into a product is to find alternate uses for it. Take baking soda. When sales for the product were in the saturation phase, manufacturer Arm & Hammer came up with a brilliant idea to take advantage of the product’s odor-absorbing properties and started an advertising campaign suggesting that customers place whole boxes of the product in their refrigerator to keep it smelling fresh.

Arm & Hammer even put a spot on the box where customers could record the date they placed it in the refrigerator, and the company recommended a regular replacement schedule. To exploit the advantages further, the firm advised customers to dispose of the old contents down the garbage disposal to keep their drains smelling fresh as well. Now you can find baking soda in a wide range of cleaning products.

Another familiar example that probably happened initially by accident is the wide use of duct tape. Initially created to be used on heating ducts, the tape is now the universal “go-to” for holding anything together. If you look around most homes, you’re sure to find a roll or two, and most likely it isn’t used for its intended purpose.

In fact, you can probably find duct tape in almost any color. The array of alternate uses for duct tape took a product with a very limited market and made it a household product.

Make improvements

Companies have become wise to the fact that, by introducing even small improvements to their product, they can entice consumers to abandon the old product even though it still provides good service and to purchase a new one. The iPhone is a familiar example.

A classic example of how incremental improvements breathed new life into a product that was in its saturation phase is the refrigerator. Although the refrigerator will probably never enter a total decline, it had reached a saturation point where most sales were replacement sales. Manufacturers have found that by continually introducing new features, they can persuade consumers to replace their refrigerator long before it stops working and actually needs replacement.

The first major feature that sent consumers back to the store was the addition of the automatic ice maker. This was followed by the side-by-side door design that facilitated putting the ice and water dispensers on the outside.

The newest design is the French-door model that fixes a major flaw of the side-by-side, which is that you can’t fit a pizza box in without significant rearranging of shelves and contents. Making these incremental improvements is a creative way to get more revenue out of a product because the improvements continuously reset the product’s position on the life cycle curve.

Change the product portfolio

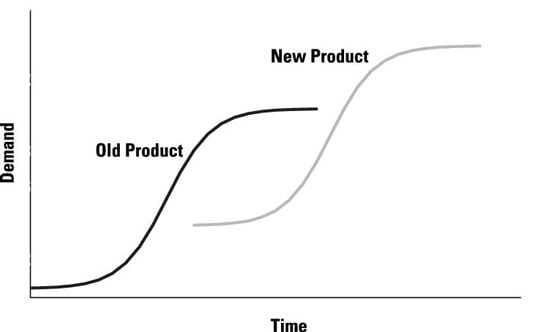

Rapidly changing technology has sped up the product life cycle and created the need for companies to introduce new products much more quickly. The computer industry has experienced these dynamics. The technology changed so rapidly at one point that a device could become obsolete within months of being purchased.

Two major risks are involved with the introduction of the new. If you introduce the new product too early, you’ll cut off sales of the old, often before full profit materializes. On the other hand, if you wait too long, a competitor may beat you to market with a new product that steals sales from your existing product.

These risks are why the timing of a new product that provides a replacement/alternative for an exiting product is such an important decision for companies in rapidly changing environments.

A key to success in this environment is to make sure that design and operations are well coordinated around the introduction of the new product. Operations employees must be well informed of the timing of new introductions because they may need to make process changes to make the new product and to reduce inventory levels of the old product before the new one hits the market.