Picking individual treasury bonds has little value and looks a lot like gambling. That’s because the markets for Treasuries are extremely efficient: So many buyers and sellers are involved, and any information worth having is so public, that any true “deal” is very hard to find.

The only really important questions you should ask yourself about Treasuries are the following:

Do I want Treasuries in my portfolio and, if so, how much?

Do I want short-term, intermediate-term, or long-term Treasuries?

Do I want inflation protection with my Treasuries?

How do I go about buying a Treasury?

Pick Your Own Maturity

Just like the question of bonds versus stocks, and government bonds versus corporate bonds, the question of maturity is largely a question of how much risk you care to stomach. In general, the more years till a bond’s maturity, the more volatile the price swings.

Not only are price swings an issue when buying a long-term bond (granted, less of an issue if you plan to hold the bond till maturity), but long-term bonds carry a much greater reinvestment risk.

In other words, if you’re holding a 20-year Treasury bond and the coupon rate is 3 percent, you have no guarantee that you’ll be able to reinvest your twice-yearly interest payments at 3 percent — at least not in anything as safe as Treasuries. If prevailing interest rates drop, you stand to lose.

Of course, the longer the term of the bond, generally the higher the coupon rate. At this particular point in history, with interest rates so low, reinvestment risk is definitely lower than it has been in the past. So choosing a maturity can be a very tricky decision. Many financial professionals suggest a compromise and going primarily with intermediate-term Treasuries (seven- to ten-year maturities).

For the individual investor, short-term Treasuries generally make sense only when the rate those bonds are paying is higher than that of money market funds and bank CDs. Sometimes that will be the case, other times not. Long-term Treasuries can be wickedly volatile, and in times of extremely low interest rates, that volatility could potentially lose you a lot of money. Shoot for the middle ground, with mostly intermediate Treasuries.

The yield curve and what it means

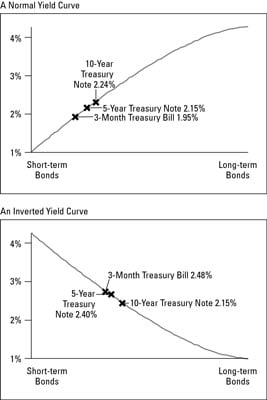

Every amateur weathercaster knows that black clouds above mean a stormy day ahead. For economists, an inverted yield curve serves as a black cloud indicating stormy economic times ahead.

An inverted yield curve simply means that short-term Treasuries are paying higher yields than long-term Treasuries. In normal times, longer-term bonds pay higher interest rates than short-term bonds. That’s because investors demand higher returns for agreeing to tie up their money for longer and to take the inherent risks that doing so involves.

Why might things occasionally turn on their head? The common belief is that inverted yield curves result when bond buyers collectively get nervous about the economic future. To alleviate their anxiety, they commit their money to long-term bonds. That way, they figure, when things tank and interest rates drop (as they often do in times of recession), their existing bonds will be worth more.

Are bond buyers right? Can they foretell a recession coming? Historically, the answer is sometimes yes and sometimes no. While an inverted yield curve has preceded a number of recessions, there have also been times, such as in 1995 and again in 1998, when yield-curve inversions were followed by a decidedly robust year.

Like all other economic indicators, the bond yield curve, although better than tea leaves at predicting the future, is far from perfect.

Here is what a normal bond yield curve looks like and what an inverted one looks like. Note that what you’re looking at, unlike a stock chart, does not show price movements over time. Rather, it shows the current interest being paid on short-term bonds versus long-term bonds.

Add in some inflation protection

The current yield on a traditional ten-year Treasury is about 2 percent. The yield on ten-year TIPS is about zero, but the principal on TIPS will be inflation-adjusted as the years go by. Look at each. Compare. All things being equal, if inflation runs at 2 percent or greater, I’ll do better with TIPS. If inflation falls beneath that point — the break-even point — conventional Treasury bonds will do better.

What’s your best investment? Who the heck knows?

Unless you can tell the future and predict interest rates and inflation (um, you can’t), you want both traditional bonds and inflation-protected bonds in your portfolio.