Catch and hold the sick chicken

The first step in examining your sick chicken is catching it and then holding it so you can start the examination. Because heat stress is often deadly for sick chickens, you want to hold off on catching and holding a sick chicken until a cooler part of the day, if possible.If it’s an emergency and you must examine a sick chicken during the hottest part of the day, do it quickly and do it in a cool spot, such as in the shade or in an air-conditioned room.

Here are three options for catching your patient:

- Easy method: Wait until dark to catch and examine a suspected sick chicken. Chickens have poor nighttime vision and don’t move around much in the dark. In dim light, you can simply lift the bird off a perch with little fuss and carry the bird into a well-lit place for the exam.

-

Tame chicken method: You may not have the luxury of waiting until dark to catch a chicken, but that’s okay, because picking up an alert chicken who is in a decent mood isn’t a huge challenge. Chickens who are used to being around people are usually very easy to catch and hold.

Shoo them gently into the corner of the coop or pen, and catch your suspect bird by reaching both of your hands over her back and holding the wings down to restrain her. Then, move one of your hands down the front of the bird and under the abdomen and pick her up.

You can carry her that way: one hand on her back and the other under her belly with your fingers between the legs. If you tuck her head loosely under your arm, she’ll feel safer and be calmer.

-

Wild chicken method: You may be in for a backyard rodeo if the chicken you’re trying to catch isn’t used to people or has a bad temper. You can catch ill-mannered roosters or wild hens with a net or a poultry hook, which is a pole about 4 feet long with a handle on one end and a hook on the other. You can purchase nets and poultry hooks from poultry supply companies.

Although a healthy chicken can be carried upside down by the legs without physical harm, a bird is scared by being handled that way. Don’t carry a sick chicken by the legs. It’s too stressful, and the bird can regurgitate food from the crop and inhale it, which can be fatal.

Examine the chicken's head

When you examine the head area, the less you restrain the bird, the better. You don’t need to grab the chicken tightly or hold the chicken’s head still to get a good look. Let the chicken stand or sit on a flat, level surface, like a table or workbench, where you don’t need to bend over. Look for these clues of chicken health problems:-

Swelling of the comb, eyelids, face, or wattles

-

Scabs anywhere on the head

-

An eye that is cloudy, goopy, or squinting. You also want to look for an irregularly shaped pupil. The pupil should be round and black.

-

Crusty or runny nostrils

-

A beak that looks twisted to the side or has cracks. The upper and lower beaks should meet at the tips.

Evaluate the respiratory system and overall body condition

During your examination of the bird’s head, the chicken hopefully settled down a little from being caught and carried. Now that the chicken is standing or sitting relaxed on the table, with only light restraint from you, take a look at how the bird is breathing.You can hardly notice normal breathing. A chicken with respiratory problems breathes with an open mouth, and the tail may bob up and down with each breath.

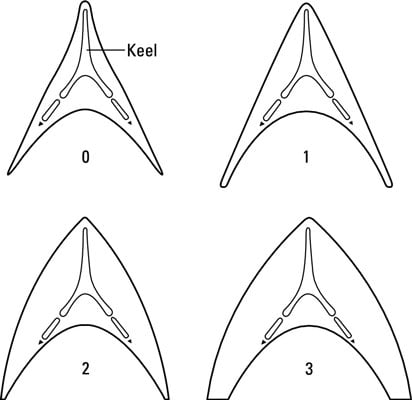

If the problem is in the upper part of the respiratory system, such as in the nostrils or windpipe, breathing may become easier as the bird relaxes. If the problem is in the lower part of the respiratory system, such as in the lungs or air sacs, open-mouth breathing and tail bobbing will continue even after the bird relaxes.Next, feel the keel (breastbone) to get an overall picture of body condition, to determine whether the chicken is thin or fat. Place your palm over the chest and keel of the bird. The keel sticks out from the bird’s chest and is surrounded on each side by the breast muscles. You can score the body condition of your bird by the way the keel and breast muscles feel.

| Score | Characteristics |

|---|---|

| 0 | The edge of the keel is rough, sharp, and prominent. Very little breast muscle can be felt, and the breast on either side of the keel feels hollow or concave. This bird is very thin. |

| 1 | The keel is prominent, but doesn't feel sharp. There is some breast muscle, and the breast on either side of the keel feels flat. This bird is thin. |

| 2 | The keel is less prominent, and the edge is smoother. The breast muscle is well developed. The breast on either side of the keel is rounded or convex. This bird is in good condition. |

| 3 | The keel feels smooth and not very prominent. Feeling the edge of the keel may be difficult through the plump, rounded breast muscles. This is a fat bird. |

Look at skin and feathers

To continue your examination, lift up the feathers to look at the chicken’s skin. Check for external parasites. Do you see any scurrying specks or walking dandruff? Look at the shafts of the feathers. White clumps on the feather shafts may be lice eggs.Go over the whole bird, stroking the feathers backward, to find areas of feather loss or skin that is reddened, lumpy, scabby, torn, or bruised. The color of a bruise can tell you the age of the injury. A bruise that just happened is red, and changes from purple, to green, to yellow, as it heals over three to five days.

Look at the wings, legs, and feet

The chicken should still be standing or sitting on the table. You can hold her lightly, restraining her only enough to prevent her from jumping off the table. Look at the bird’s posture.Does she put weight on both legs evenly? Are both wings tucked up on her back, or does one of the wings droop? A bird that is reluctant or unable to put weight on a leg or tuck up a wing may be in pain or have nerve damage.

Lay the chicken down on her side to examine more closely one wing, both legs, and both feet. Turn her over to the other side to examine the other wing.

The chicken will usually lie quietly if you drape a light cloth, such as a dish towel, over her head.

Extend each wing to look for swelling, cuts, or bruising. The chicken shouldn’t mind having her wings extended; if she struggles when you extend a wing, the reaction may be a sign of pain.Check the skin of the legs and feet. The scales should be smooth and straight. Upturned or rough leg scales can be a sign of mite infestation. Pay close attention to the bottoms of the feet; look for scratches, scabs, sores, or swellings.

Check the abdomen and vent

With the bird lying on her side, you can pick up the tail feathers to examine the vent area. Check for reddened, swollen, or torn skin and missing feathers. Look for blood coming from the vent or tissue protruding from it.Gently feel the bird’s abdomen. The chicken shouldn’t mind you doing so, unless she is in pain. A hen who is laying eggs has a wide, moist vent and a soft, doughy, enlarged abdomen. A firm abdomen and a small, puckered, dry vent are signs that a hen isn’t currently laying eggs. A bird with diarrhea often has soiled feathers in the vent area. Loose, pasty white or yellow droppings may be stuck to reddened or swollen skin around the vent.