Using physics, you can calculate what happens when you swerve. For example, you may be in a car or on a walk when you suddenly accelerate in a particular direction. In this case, just like displacement and velocity, acceleration, a, is a vector.

Assume that you’ve just managed to hit a groundball in a softball game and you’re running to first base. You figure you need the y component of your velocity to be at least 25.0 feet/second and that you can swerve at 90 degrees to your present path with an acceleration of 60.0 feet/second2 in an attempt to dodge the first baseman. Is that acceleration going to be enough to change your velocity to what you need it to be in the tenth of a second that you have before the first baseman touches you with the ball? Sure, you’re up to the challenge!

Your final time, tf, minus your initial time, ti, equals your change in time,

You can find your change in velocity with the following equation:

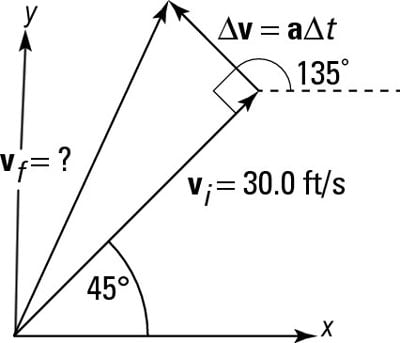

Now you can calculate the change in your velocity from your original velocity, as this figure shows.

Finding your new velocity, vf, becomes an issue of vector addition. That means you have to break your original velocity, vi, and your change in velocity,

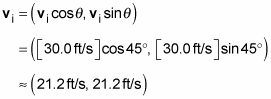

into components. Here’s what vi equals:

You’re halfway there. Now, what about

the change in your velocity? You know that

and that a = 60.0 feet/second2 at 90 degrees to your present path, as the above figure shows. You can find the magnitude of

because

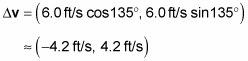

But what about the angle of

If you look at the figure, you can see that

is at an angle of 90 degrees to your present path, which is itself at an angle of 45 degrees from the positive x-axis; therefore,

is at a total angle of 135 degrees with respect to the positive x-axis. Putting that all together means that you can resolve

into its components:

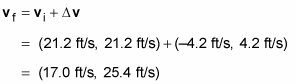

You now have all you need to perform the vector addition to find your final velocity:

You’ve done it: vf = (17.0, 25.4). The y component of your final velocity is more than you need, which is 25.0 feet/second. Having completed your calculation, you put your calculator away and swerve as planned. And to everyone’s amazement, it works — you evade the startled first baseman and make it to first base safely without going out of the baseline (some tight swerving on your part!). The crowd roars, and you tip your helmet, knowing that it’s all due to your superior knowledge of physics. After the roar dies down, you take a shrewd look at second base. Can you steal it at the next pitch? It’s time to calculate the vectors, so you get out your calculator again (not as pleasing to the crowd).

Notice that total displacement is a combination of where your initial velocity takes you in the given time, added to the displacement you get from constant acceleration.