Making a profit helps keep you in business, while maintaining a strong balance sheet ensures you can stay in business. So, make sure you understand the financial statements, record adjustments if needed, and follow some basic rules for presenting accounting information to your business’s managers, owners, investors, and creditors.

Formulas and functions for financial statements

As the accounting controller, you’re in command of your business’s accounting needs, so you need a strong understanding of the ins and outs of financial statements, including what goes on them and in what order.

If you don’t prepare them correctly, they won’t reflect a true picture of your business’s financial status. Keep the following important rules and points in mind as you prepare and use your business’s financial statements.

Accounting equation

Assets = Liabilities + Owners’ Equity

Liabilities and owners’ equity are the two basic types of claims on the assets of an entity. The two-sided nature of the accounting equation is the basis for double entry accounting that records both sides of the entity’s transactions — what is received and what is given in the economic exchange.

Financial effects of revenues and expenses

Revenue = Asset increase (debit) or Liability decrease (debit)

Expense = Asset decrease (credit) or Liability increase (credit)

Connections between income statement and balance sheet accounts

Sales revenue → Cash and Accounts receivable

Cost of goods sold expense ← Inventory

Operating expenses → Cash

Operating expenses ← Prepaid expenses

Operating expenses → Accounts payable

Operating expenses → Accrued expenses payable

Depreciation expense ← Fixed assets

Interest expense → Accrued expenses payable

Income tax expense → Accrued expenses payable

Bookkeeping cycle

In today’s economy and digital world, most of the bookkeeping cycle is handled by computers, which process vast amounts of digital data by capturing financial transactions and processing the information through original entries (in journals) and postings in the general ledger chart of accounts.

As a refresher, the following bookkeeping cycle remains intact, whether the accounting function is fully automated or completed manually:

Financial Transactions (and certain other events) → Original Entries in Journals → Postings in General Ledger Chart of Accounts → End-of-Period Adjusting Entries → Preparation of Financial Statements, Tax Returns, and Internal Accounting Reports → Closing Entries at End of Year.

Making accounting adjustments to reach profit potential

Having your business reach a profit is important; if it doesn’t, sooner or later the business will fail. As a business manager, you want to keep a close eye on the financial statements and make the necessary (and legal) accounting adjustments to your financial records as needed.

These tips can help you make the necessary adjustments to your business’s net income, eye two different profit analysis models, and communicate the reports to your managers.

Adjustments to net income for determining sash flow from operating activities

Accounts payable and accrued expenses payable are operating liabilities used in the profit-making process.

-

Operating asset increases and operating liability decreases are negative adjustments (decrease cash flow from operating activities)

-

Operating asset decreases and operating liability increases are positive adjustments (increase cash flow from operating activities)

-

Depreciation and amortization expenses are positive adjustments (increase cash flow from operating activities)

Cardinal Rule: Make all cash flow adjustments to net income; do not simply add back depreciation and amortization, which could be seriously misleading.

Two profit analysis models for management decision making

Contribution margin minus fixed expenses model:

| Sales price | $100 |

| Less variable costs per unit | $60 |

| Equals contribution margin per unit | $40 |

| Times annual sales volume, in units | 120,000 |

| Equals total contribution margin | $4,800,000 |

| Less fixed operating expenses | $3,000,000 |

| Equals operating profit | $1,800,000 |

Excess of sales over breakeven model:

$3,000,000 annual fixed operating expenses ÷ $40 contribution margin per unit = 75,000 units breakeven point (volume)

| Annual sales volume for year, in units | 120,000 |

| Less annual breakeven volume, in units | 75,000 |

| Equals excess over breakeven, in units | 45,000 |

| Times contribution margin per unit | $40 |

| Equals operating profit | $1,800,000 |

Guidelines for internal accounting reports to managers

When you’re preparing financial information for your business’s managers, follow these tips:

-

Follow the organizational structure (responsibility accounting)

-

Orient your report based on whether organization unit is a profit center or a cost center

-

Know the mind of the manager

-

Highlight significant factors and deemphasize non-significant factors

- Keep in mind the acronym CART — always prepare Complete, Accurate, Reliable, and Timely financial reports, statements, and information

Choosing an accounting method for your business

Different businesses make different accounting decisions. Some businesses choose conservative accounting methods, while others choose liberal accounting methods.

Accounting is more than just reading the facts or interpreting the financial outcomes of business transactions. It also requires accountants to choose between alternative methods and why accounting being is as much of a form of art as science.

Similar to the conservative states and liberal states addressed in politics, accounting has:

- Conservative accounting methods: These tend to delay the recording of revenue and accelerate the recording of expenses. Profit is reported slowly and, generally, at lower levels in early reporting periods.

- Liberal accounting methods: These tend to accelerate the recording of revenue and defer or delay the recording of expenses. Profit is reported quickly and, generally, at higher levels in early reporting periods.

In general terms, conservative accounting methods are pessimistic, and liberal methods are optimistic. The choice of accounting method also affects the values reported for assets, liabilities, and owners’ equities in the balance sheet.

Accounting methods must stay within the boundaries of Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP). A business can’t conjure up accounting methods out of thin air. GAAP isn’t a straitjacket; it leaves plenty of wiggle room. But the one fundamental constraint is that a business must stick with its accounting method once it makes a choice. If the business elects to change the accounting method, it must be fully and clearly disclosed.

Consistency is the rule; the same accounting methods must be used year after year. The Internal Revenue Service allows businesses to change their accounting methods once in a while, but the justification has to be persuasive.

A new business with no accounting history has to make accounting decisions, such as the following, for the first time:

- If the business sells products, it has to select which cost of goods sold expense method to use.

- If the business owns fixed assets, it has to select which depreciation method to use.

- If the business owns intangible assets, such as patents, it has to select an appropriate method to amortize the value of the intangible asset.

- If the business makes sales on credit, it has to decide which bad debts expense method to use.

- If the business offers a product warranty, it must establish a reasonable method to estimate future warranty claims for current products sold.

The choices of accounting methods for these five expenses — cost of goods sold, depreciation, amortization, warranty, and bad debts — can make a sizable difference in the amount of profit or loss recorded for the year.

Choosing conservative accounting methods for these three expenses can cause profit for the year to be lower by a relatively large percent compared with using liberal accounting methods for the expenses.

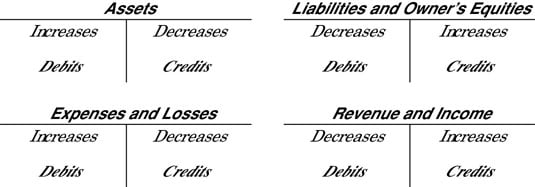

Knowing your debits from your credits

Accountants and bookkeepers record transactions as debits and credits, while keeping the accounting equation constantly in balance. This process is called double-entry bookkeeping. Double-entry bookkeeping records both sides of a transaction — debits and credits — and the accounting equation remains in balance as transactions are recorded.

For example, if a transaction decreases cash $25,000, then the other side of the transaction is a $25,000 increase in some other asset, or a $25,000 decrease in a liability, or a $25,000 increase in an expense (to cite three possibilities).

The illustration below summarizes the basic rules for debits and credits. By long-standing convention, debits are shown on the left and credits on the right.

An increase in a liability, owners’ equity, revenue, and income account is recorded as a credit, so the increase side is on the right. The recording of all transactions follows these rules for debits and credits:

Notice the horizontal and vertical lines under the accounts in the illustration above. These lines form the letter T. Although the actual accounts maintained by a business don’t necessarily look like T accounts, they usually have one column for increases and another column for decreases. In other words, an account has a debit column and a credit column.

Also, an account may have a running balance column to continuously keep track of the account’s balance. While T accounts represent an old school accounting concept (back in the days when accountants wore green eye shades and had no personalities), they do drive home a key concept in accounting related to ensuring debits and credits are properly recorded.

Practically everyone has trouble with the rules of debits and credits. The rules aren’t very intuitive, but learning them is a rite of passage for bookkeepers and accountants. The only way to really understand the rules is to make accounting entries — over and over again. After a while, using the rules becomes like tying your shoes — you do it without even thinking about it.

Classification of business transactions

In understanding accounting, you need to be very clear about which classification of business transaction you’re looking at. Almost all businesses are profit-motivated, so one basic type of transaction is obvious: profit-making transactions. In a nutshell, profit-making transactions consist of generating sales revenue and incurring business expenses.

A business may have other income in addition to sales revenue, and it may record losses in addition to expenses. But the bread and butter profit-making activities of a business are generating sales and controlling expenses. The profit-making transactions of a business over a period of time are reported in its income statement.

A business’s other transactions fall into three basic categories:

- Set-up and follow-up transactions for sales and expenses: Includes collecting cash from customers after sales made on credit are recorded; the purchase of products (goods) that are held for some time before being sold, at which time the expense is recorded; and making cash payments for expenses some time after the expenses are recorded.

- Investing activities (transactions): Includes the purchase, construction, and disposals of long-term operating assets such as buildings, machinery, equipment, and tools or investing in intangible assets, such as patents, or acquiring goodwill.

- Financing activities (transactions): Includes borrowing money and repaying amounts borrowed; owners investing capital in the business and the business returning capital to them; and making cash distributions to owners based on the profit earned by the business.

Investing and financing activities of a particular period are reported in that period’s statement of cash flows. In contrast, set-up and follow-up transactions for sales and expenses stay in the background, meaning that they are not reported in a financial statement. Nevertheless, these transactions are essential to the profit-making process.

Consider, for instance, the purchase of products for inventory. As far as profit is concerned, nothing happens until the business makes a sale of that inventory and records the cost of goods sold expense against the revenue from the sale. Because the business needs to have the products available for sale, the purchase of inventory is the important first step, or set-up transaction.