If you’re working in a services supply chain, try not to get hung up on the word make. Just remember that the point of any make process is to transform inputs such as raw materials and technical skills into outputs for a customer. For a doctor, the make process would be performing a surgical procedure. For an artist, it would be creating a painting.

Planning production

Before you can create a good production plan, you need to take a lot of factors into account. Here are 10 examples of the kinds of information that you really, truly need to consider before you can tell whether a production plan will work:- Determine when customers need the product and whether they’re waiting for it now.

- Determine how long it’ll take you to make the product.

- Determine the capacity of your manufacturing process.

- Determine the setup time required to make the product and whether that time will affect the setup time for other products.

- Determine how to prioritize the order in which you’ll make products.

- Determine what parts, components, or supplies you need to have on hand so that you can make a particular product.

- Determine whether you already have the parts you need or have to order them.

- If you must order parts, determine the supplier’s lead time and the shelf life of the products.

- Identify risks that could disrupt production.

- Determine whether you need to schedule time for breaks, holidays, changeovers, and equipment maintenance.

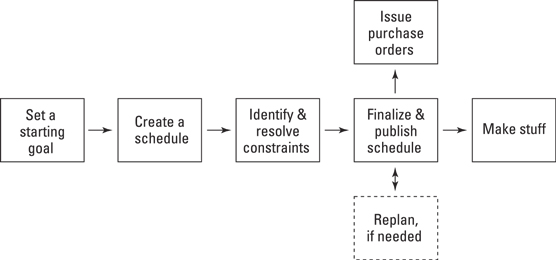

Production scheduling process flow

Production scheduling process flowSetting a demand goal

Production planning starts with a high-level goal: how much you want to sell. You can think of this goal as the “in a perfect world” scenario. If you think you’ll have 1 million customers next month in your fast-food restaurant, you’d start with a demand goal of 1 million hamburgers. This high-level demand goal is called the master demand schedule (MDS). It’s okay if your MDS is optimistic, but try to keep it reasonable. There’s no point in building a production plan for a sales target that you’d never be able to meet.Creating a production schedule

After determining your demand goal, you break that sales goal down into a master production schedule (MPS). In other words, building the MPS is how you to decide what you’ll need to make each day to meet the MDS goal. Creating an MPS forces you to look more closely at the materials you need and when you need them. It also drives you to look at the people and equipment you have available to make your products.As you build your MPS, you begin to uncover production constraints, which are bottlenecks or problems that may interfere with production. You may not be able to order as much of the raw materials as you want because your suppliers don’t have enough capacity, for example. Or perhaps your manufacturing equipment can’t produce the materials quickly enough. In the example of a fast-food restaurant, two obvious constraints that the MPS will need to address are space and time. You have a limited amount of room to store buns, meat patties, and lettuce, and these ingredients are perishable, so you need to use them before they spoil.

Each constraint that you find requires you to make some decisions. You need to consider whether you can do something to resolve or eliminate the constraint, such as find a new supplier or rent extra storage space. Or you may need to change your production schedule. It’s common to repeat this constraint resolution process several times, because each time you change the MPS to resolve a constraint, you need to check whether that change affects other constraints. In other words, production scheduling is an iterative process.

Finalizing the production schedule

When you know what materials you need to order, and you’re confident that they can be delivered on time, you can finalize, publish, and execute your production schedule. The final production schedule gives your team its actual production targets: how much you expect to make and when you expect to make it.Your production schedule also drives purchase orders to authorize buying the components you need from your suppliers. The schedule may be broken into jobs or batches of products that are similar or that are being made for the same customer. When the jobs are scheduled, you can sequence the delivery of parts so that they show up just in time (JIT) for you to use them.

Lean Manufacturing often combines parts sequencing and JIT deliveries. In an automotive assembly plant, for example, many kinds of upholstery are used for car seats, so the seats are sequenced to show up in a particular order and are delivered to the assembly line JIT.

If everything works properly, your production schedule won’t change and should be stable. But things don’t always work that way. Even after the production schedule is published, there’s a good chance that you may end up making changes if things don’t go as you expect — if a shipment of supplies gets delayed or a machine breaks down, for example.When you revise the schedule, you may have to change the order of production jobs or adjust your production targets. This replanning also affects both your suppliers and your inventory levels, because it changes the order in which you use each component. Because so many activities are driven by the production schedule, frequent replanning can cause confusion and frustration. A production schedule that changes too often is called a nervous schedule.

Nervous production schedules create waste in a supply chain, such as unnecessary work and excess inventory.

Most companies make a choice about how far in advance they can realistically change the production schedule without creating chaos for their supply chain. This threshold, usually measured in days or weeks, is called a time fence.A company might decide that it’s okay to make a change to the production schedule with at least one week’s notice. In this case, it would be possible (but not desirable) to make changes to the production schedule outside the one-week time fence. But when the company crosses that time fence — is less than one week out from a production run — the schedule is frozen, and no more changes will be allowed.

The earlier in the process you can identify a constraint and replan the production schedule, the better off you’ll be. In most cases, changing the production schedule after you’ve already issued purchase orders for the supplies means that you’ll end up with extra inventory, which increases your costs.

You can think about the challenge of production scheduling for a fast-food restaurant. Suppose that something unexpected happens: You sell fewer burgers than you expected, everyone asks for extra pickles, or there’s a recall on lettuce. In each case, you need to see whether these differences change your goals or create constraints; if they do, you’d need to replan your production schedule.Your production targets should always be aligned with your sales goals to ensure that you aren’t making too much or too little to satisfy your customers. This process is called sales and operations planning.

In the old days, people prepared and updated production schedules manually, which was a complex, time-consuming process. Today, most companies update schedules automatically by using material requirements planning software.

Capacity

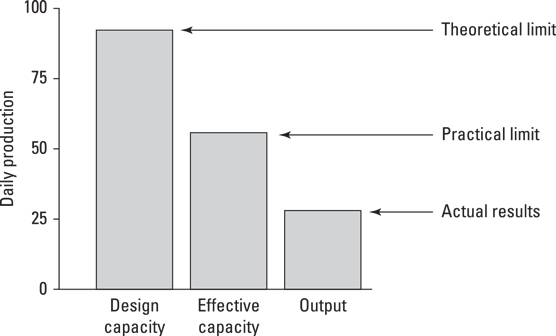

Every person, every group of people, and every machine in the world has a limit to how much it can process or produce in a particular amount of time. Whether you’re in the business of manufacturing bottles or delivering babies, you refer to this limit as your capacity. There are lots of ways to measure and define capacity, but when you strip away the fluff, every supply chain manager needs to understand three concepts because they factor into your production plan: design capacity, operating capacity, and capacity utilization.Design capacity

Design capacity (or theoretical capacity) is the maximum that a machine (or person) can possibly produce. The design capacity of your imaginary fast-food restaurant is the amount you could make if every person and every machine were running continuously, every minute of every day. That capacity might mean a whole lot of hamburgers and French fries but still isn’t infinite.Operating capacity

Let’s be real: Most processes don’t run at their design capacity (at least not for very long!). People need to take breaks. Facilities shut down for shift changes. It takes time to perform equipment maintenance and software upgrades. When you take all these constraints into account, you end up with a new limit on how much you can make, which is much lower than your design capacity. This limit is called your operating capacity (or effective capacity).Unless you’re making only one product over and over, you probably need to shut down some machines and make changes between jobs, such as switching tools or bringing in different components. This setup time affects how much operating capacity is available for making products. And, of course, things can go wrong: A machine could break down, you could run out of inventory, or someone could be late for a shift. Any of these issues — and many others — can slow a manufacturing process, and all of them eat away at your efficiency.

Because you could never possibly make more of a product than your design capacity would allow, the design capacity is technically one of your production constraints. Because operating capacity is almost always lower than design capacity, however, it’s rare for a process to be constrained by the design capacity.

Operating capacity is one of the main constraints on production. In many cases, you can do things to increase operating capacity, such as running extra shifts or changing your maintenance procedures. Therefore, you may have some flexibility when managing the operating capacity for your production plan. A common goal for supply chain managers is to increase operating capacity and get it as close as possible to the design capacity.

Capacity utilization

With all the factors that can constrain production, the actual output of a manufacturing process is often a fraction of how much you think it could make. A common way to measure production output, or yield, is the percentage of operating capacity that you actually use. This percentage is called capacity utilization. If your process is running at full speed, making as many widgets as it possibly can, your capacity utilization is 100 percent.The U.S. Federal Reserve tracks industrial production and capacity utilization across various business sectors as a way to measure how well the economy is doing. Find the latest capacity utilization rates.

A common goal of supply chain management is to increase capacity utilization. The more capacity you use, the more products you’re producing and the more money you’re able to make with the assets you have.

You can see how these concepts are related by looking at the fast-food restaurant example. The number of burgers that you make is your production output, which is a smaller quantity than your operating capacity, which in turn is smaller than your design capacity. This figure illustrates the relationship of production output (capacity utilization) to operating capacity and design capacity. Manufacturing capacity and output

Manufacturing capacity and outputIncreasing capacity utilization always sounds like a good idea at first. But when you look at it more closely, sometimes it can increase your costs and decrease your efficiency. Your car, for example, probably has the capacity to drive at 100 miles per hour, but it gets much better gas mileage at closer to 50 miles per hour. (Let’s ignore traffic laws for a second and focus on the mechanical issues.) In addition to burning more gas, driving your car at 100 miles per hour is going to cause many of the parts to wear out more quickly, and it gives you less time to react to a pothole in the road.

So, even though the car has the capacity to go faster if you need it to, you’ll probably choose a slower pace for day-to-day commuting. In other words, you’ll decide that it’s better, overall, to operate your car well below its design capacity.

In the same way, manufacturing processes often become less efficient when they get close to their capacity limits. One obvious reason is that equipment may wear out faster, which causes breakdowns. Also, increasing capacity utilization (in other words, making more products) can create an inventory problem if the rest of your supply chain can’t keep up.

Your real goal as a supply chain manager is to make only as many products as your customers will buy — to provide enough supply to meet demand. If your output is high, but your sales are low, increasing manufacturing capacity utilization means that you’ll build up unneeded inventory and tie up your company’s cash, which is bad for the supply chain.

The goal of production planning and scheduling is to make as many products as your customers will buy at the precise time that they need them. Building your production schedule around customer demand and your supply chain’s constraints ensures that you use your capacity efficiently while keeping your inventory as low as possible.